The City and the City is a 2009 weird fiction/crime novel by China Miéville, following Detective Tyador Borlú from the eastern European citystate of Besźel. Borlú's murder investigation brings him from Besźel to the overlapping citystate of Ul Qoma, a city that "grosstopically" exists alongside or on top of Besźel; not through an alternate dimension or plane of existence, but literally existing right alongside it. Citizens of the cities are not allowed to acknowledge, see, or even hear each other, or they are at risk of "breaching" and being vanished away by the mysterious power of Breach. The concept is fascinating, like all Miéville's work. I adore the way he takes such a specific, outlandish concept and develops the worldbuilding around it.

The City and the City is a 2009 weird fiction/crime novel by China Miéville, following Detective Tyador Borlú from the eastern European citystate of Besźel. Borlú's murder investigation brings him from Besźel to the overlapping citystate of Ul Qoma, a city that "grosstopically" exists alongside or on top of Besźel; not through an alternate dimension or plane of existence, but literally existing right alongside it. Citizens of the cities are not allowed to acknowledge, see, or even hear each other, or they are at risk of "breaching" and being vanished away by the mysterious power of Breach. The concept is fascinating, like all Miéville's work. I adore the way he takes such a specific, outlandish concept and develops the worldbuilding around it.

It's kind of a boring book.

In 2018, the BBC released a limited series adaptation of the novel, split into four hour-long episodes. I only learned about it after looking up the book once I'd finished reading it, and along with my partner we started watching it that very night.

In 2018, the BBC released a limited series adaptation of the novel, split into four hour-long episodes. I only learned about it after looking up the book once I'd finished reading it, and along with my partner we started watching it that very night.

Language often features heavily in Miéville's books - the main character of The Scar is a translator, Embassytown revolves entirely around the complications of the native alien's language - so I was pleased to see that carried over to The City and the City. The citizens of Besźel speak Besź and the Ul Qomans speak Illitan. Borlú speaks both, along with English, and throughout the book he switches between all three languages easily. I was very interested to see how the show would handle the visuals of "unseeing" a whole street right next to you and they do this by just blurring out Ul Qoma/Besźel when necessary, which works fine, but I was extremely interested to see how they'd handle the language-switching. Here's the opening to Chapter 5 of The City and the City:

"If you do not know much about them, Illitan and Besź sound very different. They are written, of course, in distinct alphabets. Besź is in Besź; thirty-four letters, left to right, all sounds rendered clear and phonetic, consonants, vowels and demivowels decorated with diacritics - it looks, one often hears, like Cyrillic (though that is a comparison likely to annoy a citizen of Besźel, true or not). Illitan uses Roman script. That is recent.

"Read the travelogues of the last-but-one century and those older, and the strange and beautiful right-to-left Illitan calligraphy - and its jarring phonetics - is constantly remarked on. At some point everyone has heard Stern, from his travelogue: 'In the Land of Alphabets Arabic caught Dame Sanskrit's eye (drunk he was despite Muhamed's injunctions, else her age would have dissuaded). Nine months later a disowned child was put out. The feral babe is Illitan, Hermes-Aphrodite not without beauty. He has something of both his parents in his form, but the voice of those who raised him - the birds.

"The script was lost in 1923, overnight, a culmination of Ya Ilsa's reforms: it was Atatürk who imitated him, not, as is usually claimed, the other way around. Even in Ul Qoma, no one can read Illitan script now but archivists and activists.

"Anyway whether in its original or later written form, Illitan bears no resemblance to Besź. Nor does it sound similar. But these distinctions are not as deep as they appear. Despite careful cultural differentiation, in the shape of their grammars and the relations of their phonemes (if not the base sounds themselves), the languages are closely related - they share a common ancestor, after all. It feels almost seditious to say so. Still."

So that's a good lump of information about these two languages, and an interesting challenge to bring to the screen. How did they do?

Illitan (and to an extent Besź) as it appears in the show was created in collaboration with Dr Alison Long, a linguistics professor at Keele University with a specialisation in Slavonic** languages. Illitan appears as a fully realised conlang (using the Georgian alphabet rather than a conscript - more about this later) but Besź, as the language of our viewpoint character, is plain English with Cyrillic flair added for any written text. Borlú is no longer bilingual; he understands only a couple of Illitan words (like "wanker", #epic) and I think in any moment where a character is actually speaking English they don't specify whether they're speaking English or Besź to keep it simple.

In 2019, Long gave a talk about her work on The City & the City at the 9th Language Creation Conference, hosted by the Language Creation Society. The full talk is available as part of this livestream (it starts at 2:51:44) but the audio is quite poor. I'm insane and transcribed all the relevant parts; you can read the full transcription here and I'll be referencing it fairly often, but there might be a couple of misheard lines here and there (I only listened through the once and did my best). With all that in mind, I'll cover Besź before we get into Illitan.

Part 1: Besźel

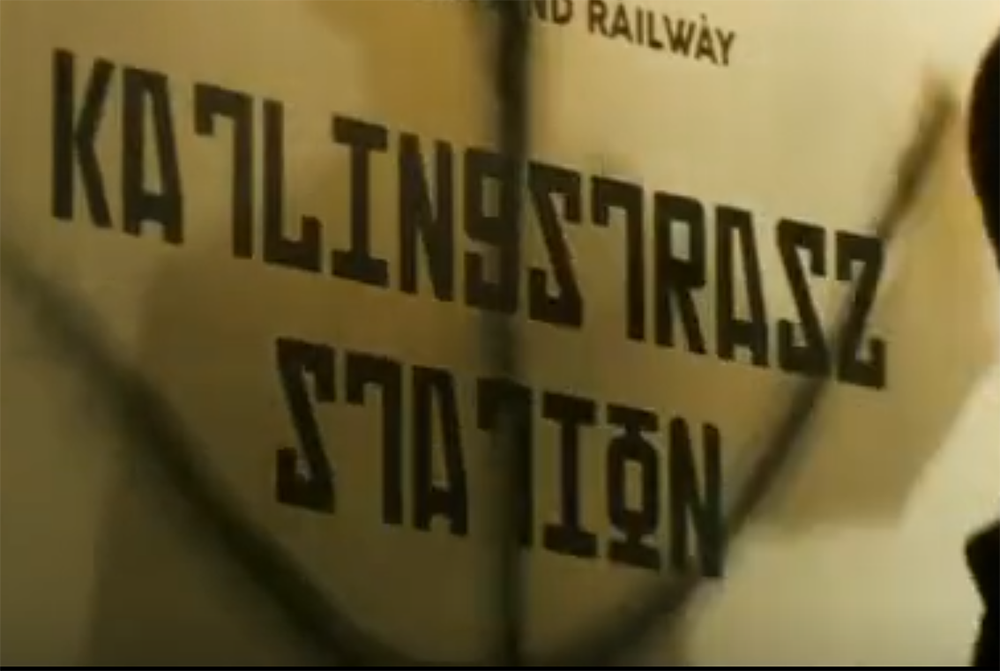

In the book, street names are constructed by compounding a name and the word strász, such as GunterStrász or UropaStrász, which feels quite Germanic. All the Besź characters' names feel like they authentically belong to a European language: Stepen for "Stephen", Vilyem for "William", Lisbyet for "Elizabeth". We get very few other words in Besź, but what we do have feel heavily influenced by the Germanic languages; I'm not going to reread the book to double-check this, but on a quick flick through here were the other Besź words I could find:

- policzai, "police"

- seqyestre, "half-arrest", which very clearly feels like it shares a root with English "sequester"

- Inkyistor, the name of a newspaper and also clearly sharing a root with English "inquisitor" or something similar

- Iy Déurnem, another untranslated name of a newspaper***

- Besźmarques, the currency, which sounds suitably similar to Deutschmarks

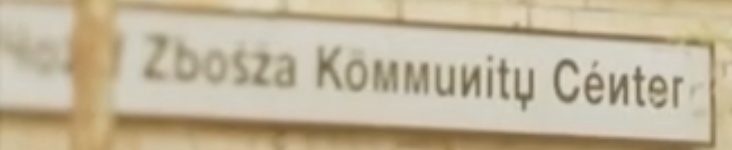

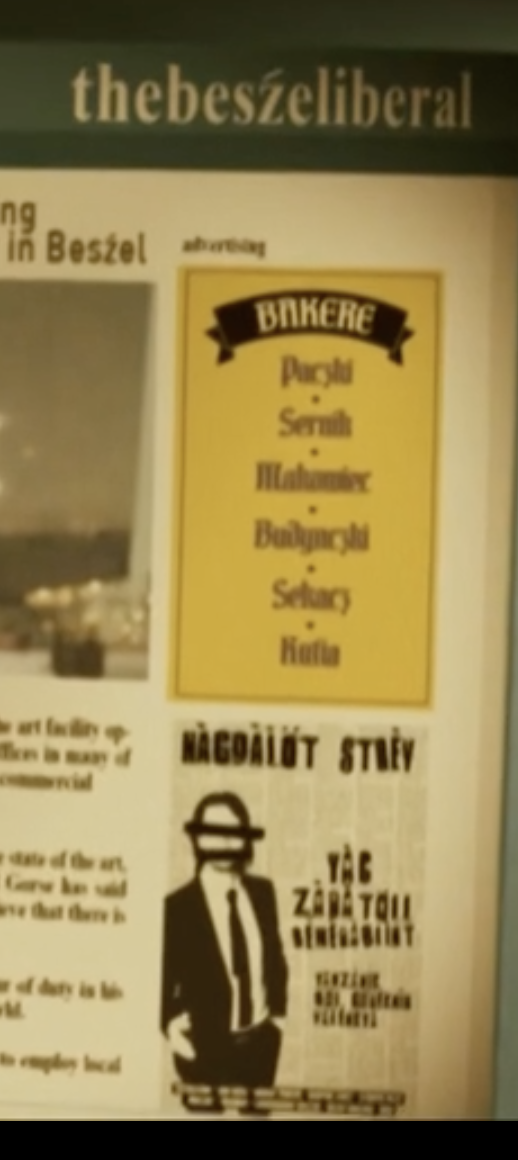

In the show it is immediately noticeable, to a laughable degree, that they took "Besź looks like Cyrillic" very literally. The fonts chosen to represent Besź are clearly designed to invoke Soviet imagery, with their thick, faux-Cyrillic letters. Nearly every word is jammed full of diacritics, trying to make everything feel foreign while leaving it readable for an English speaker. In her talk, Long said: "I got into trouble for this and I apologise to any Slavicists in the room - we had to use fairly random-looking diacritics. [...] That wasn't my decision, but native English speakers (and that's the majority of the BBC audience) needed to be able to understand what was all written in Besźel. [...] So they know better than I do, what works on TV, so I left them to it." (X)

My partner and I had a lot of fun exclaiming over the unnecessary diacritics, but they don't always appear in all text. Some Cyrillic-esque fonts have no diacritics, but if it's in a Roman font then it's usually drowning in them. And that got me thinking, well, is there a pattern to this? Almost certainly not. Can I make one up? I can sure as hell give it a go. I'm crazy but I'm not stupid: I know there was very little intentionality behind the diacritics other than making the text visibly foreign. But a guy can have fun, can't he?

He sure fucking can. I'm going to look at the Besź in this show as if it's the actual, intended representation of the language.

Besź corpus

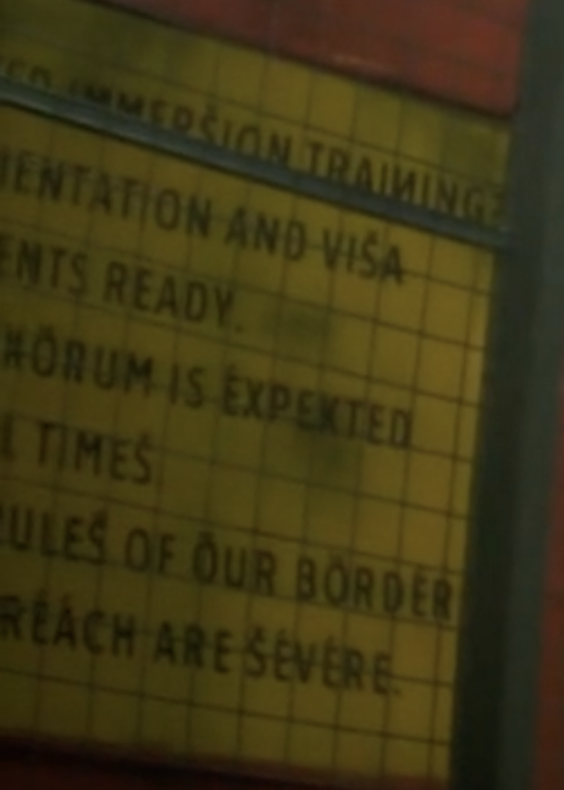

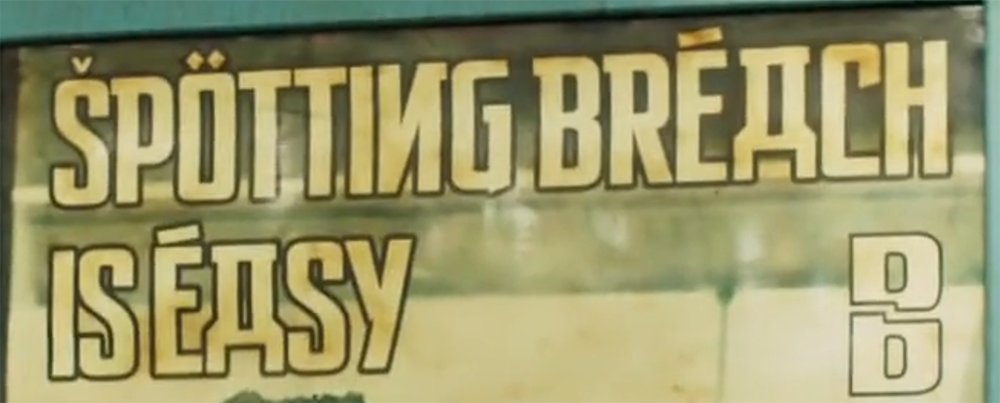

Let's look at some examples! Here's our corpus of Besź text, screenshot from all four episodes and arranged in groups (click to expand each image). Whenever I refer to Cyrillic from here on, I'm specifically talking about "Cyrillic": fonts that use elements of Cyrillic that English-speakers would recognise as such. In the transcriptions, if a letter has an accent but I can't make out what it is, I've marked the letter in orange.

Transcriptions: ☟

- DÖPLIRCAFFĒ: БALAL & KÖSБER

- Zbosza Köммuиitч Céиter

- YOU ARE ИÖW LEAVING BÈŠZÈL - BE SAFE

- [---] IMMERŠION TRAIИING?

[---]ENTATION AND VIŠA

[---]ENTS READY.

[DE]KÖRUM IS ÉXPEKTED

[---]TIMEŠ

[---]ULEŠ OF ÖUR BÖRDÉR

[---]RÉÁCH ARE ŠÉVÉRE. - ŠPÖTTIИG BRÉДCH IS ÉДSY

Transcriptions: ☟

- KATLINGSTRASZ STATION

- PLATFORMS 1-5

- TICKETS

- HOW TO USE

- PнenoмenoLogч of Дppearances

Transcriptions: ☟

- THIS GIRL WÁS FÖUND DÉÁD ÁT BULKYÁ SÖUND

IF YÖU HÁVÉ ÁNY INFÖRMÁTIÖN

CÁLL THÉ PÖLIZÁI ÖN 91-902-182 - Càšé Nö:

- TRUŠT IN BRÉACH

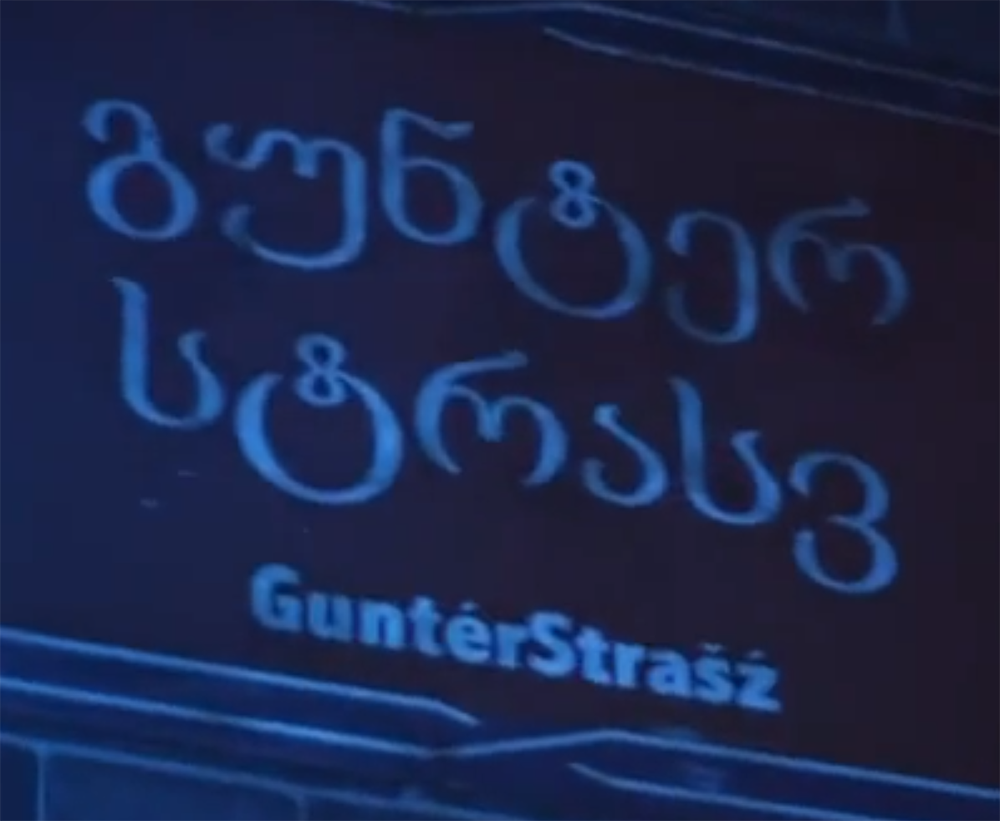

- GuntérStrašź

- INŠPÉKTÖR TYÁDÖR BÖRLU

- [H]AVE YÖU KÖMPLETED [---]

HAVE [YOUR ORIENTATION] [---]

DÖKUM[ENTS] - TRÀNSPÖRT

- KÖMMIŠŠÁR GÁDLÉM

- DÖ YÖU KNÖW THIS GIRL?

- BORDÉR KONTROL

- TÖURIŠT TRÀINING

- EXIT

- TĀXI

- [OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE]

- UNIFICATIÖN - ÖNE CITY

- KÉÉP ÖUT DIŠPUTÉD ZONÉ

- VÖTÉ NÖW

- VulkövStrašź

- W[EL]KÖME TO BÈŠZÈL.

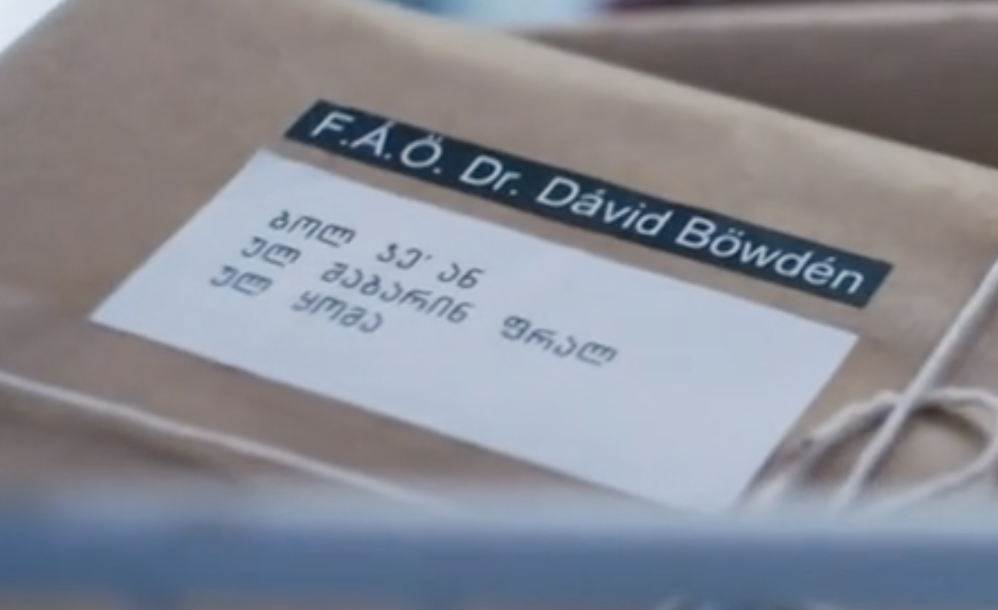

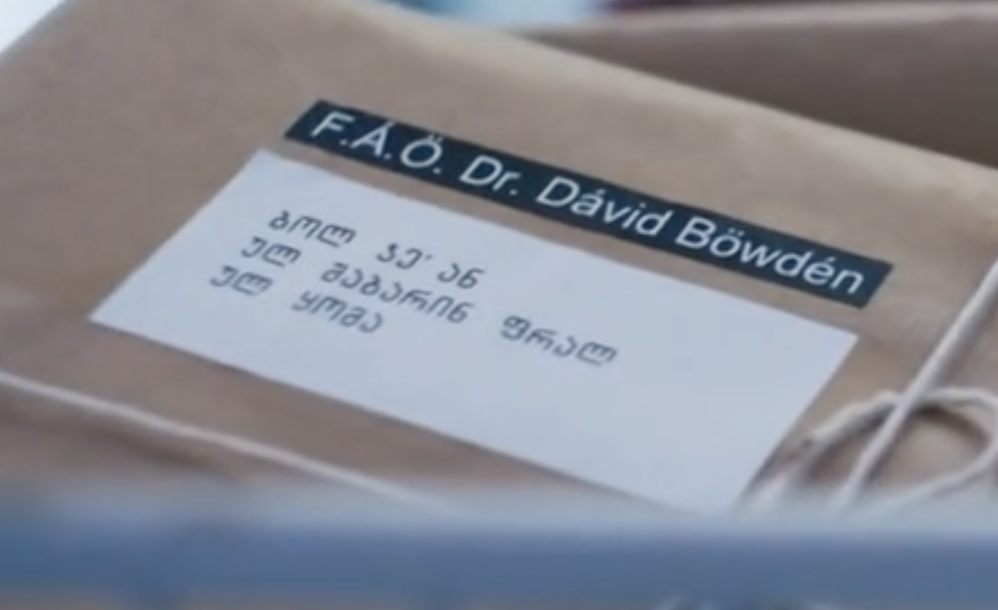

- F.Á.Ö. Dr. Dávid Böwdén

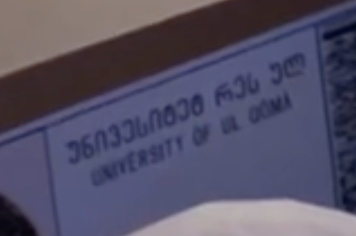

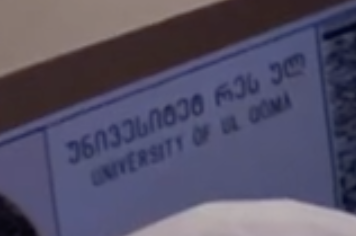

- UNIVERSITY OF UL QOMA

- BÉŠZÉL

TRÀNŠPÖRT [A]ND RÀILWÀY - MISSING PERSONS: Katrynía Perla

- LIFT[Ŝ]

- UL QOMA BÖRDER KÖNTRÖL

- BÉŠZÉL BÖRDER KÖNTRÖL

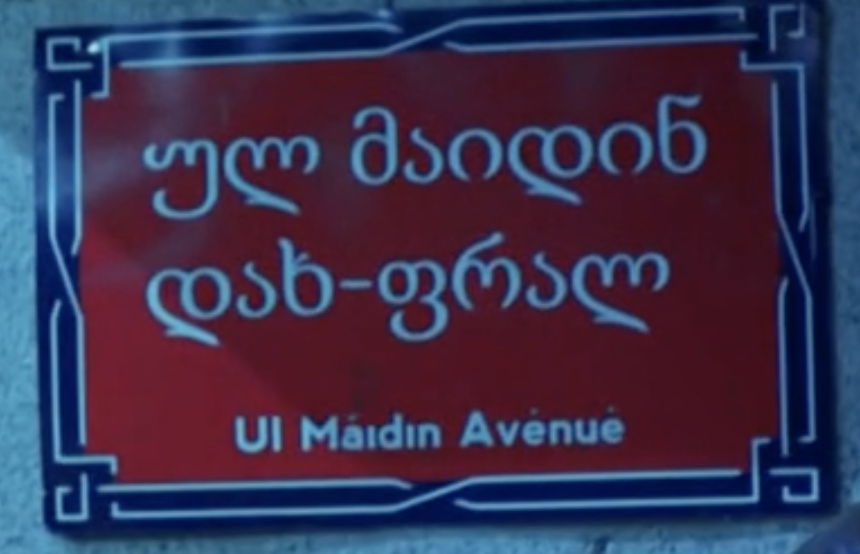

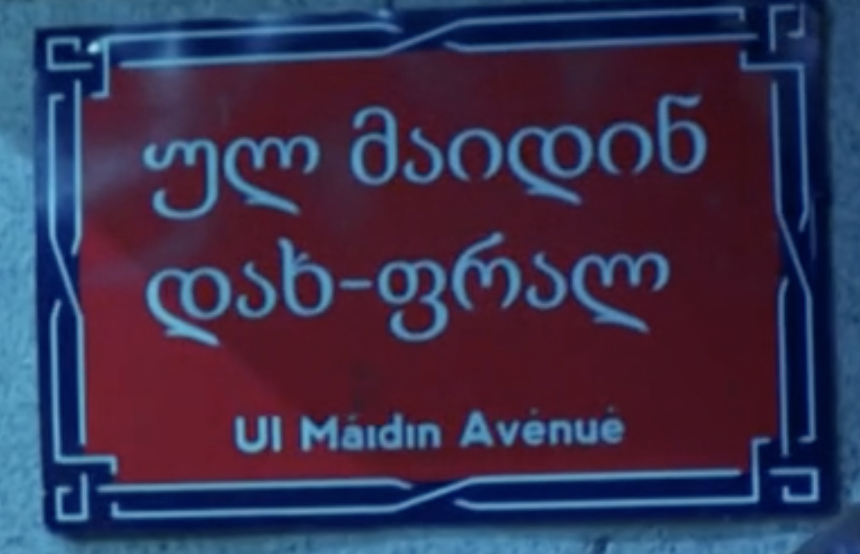

- Ul Máidin Avénué

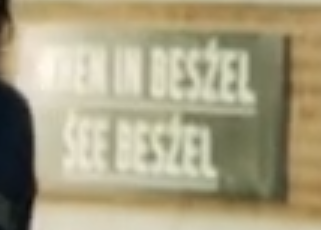

- WHEN IN BESŹEL

[Ŝ]EE BESŹEL - POLIZAI

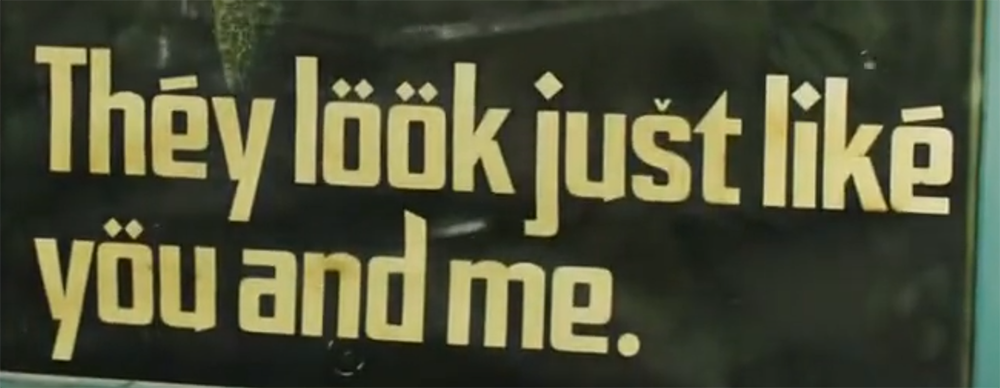

BESZEL - Théy löök jušt liké yöu and me.

- BESŹEL

Transcriptions: ☟

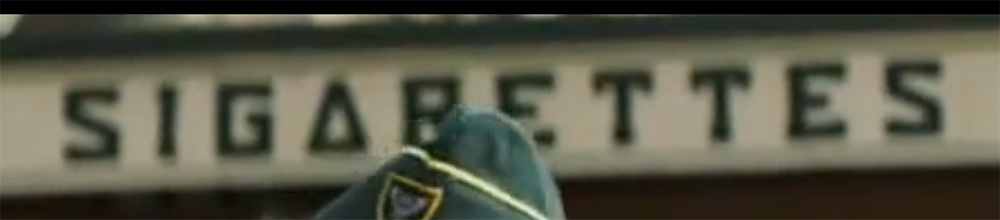

- SIGARETTES

- PROSPEKT ALLAT

- FUNICULAR

FUNICULAR PARK WEST

FUNICULAR PARK EAST

RIKALFI

BODINOV

MIGARYAN

VENCELAS - NO UNAUTHORISED ACCESS

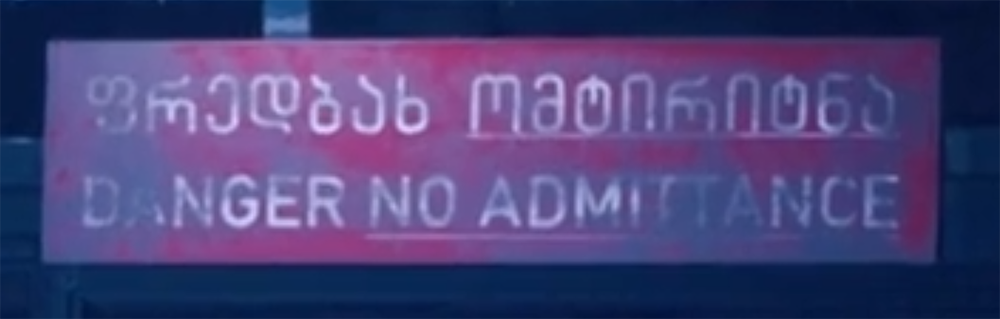

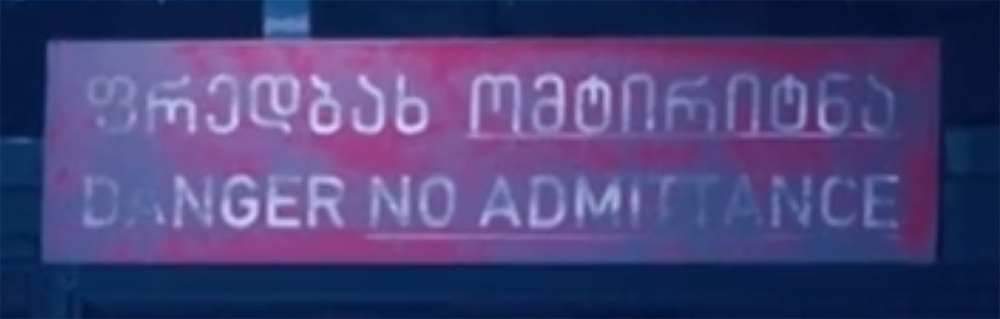

- DANGER NO ADMITTANCE

- POLIZAI

- POLIZAI

Besź analysis

Firstly, there are a few differences between the book's Besź and the show's Besź:

| Book | Show |

|---|---|

| Tyador Borlú | Tyádör Börlu |

| Commissar Gadlem | Kömmiššár Gádlém |

| GunterStrász | GuntérStrašź |

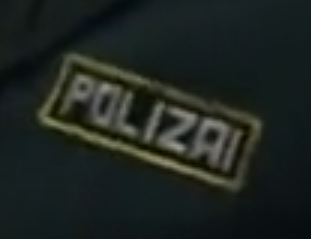

| policzai | polizai |

Borlú's name has been zhuzhed up with all these extra diacritics... but the one accented letter from the book is gone. The only time we see his name written anywhere is on his door, so it may be that there is a case system in Besź.

- Borlú - nominative, where his the subject in a phrase, and vocative case, addressing him directly

- Börlu - genitive, or maybe even locative? Borlu's door, or "at Borlu" because that's where you can usually find him.

Following from that, we can assume that Gadlem is the nominative/vocative and Gádlém is the genitive/locative. Corwi is Borlú's partner never has her name written in the show, but let's extrapolate: Borlú becomes Börlu, so Corwi becomes Cörwi. We have more evidence for this: David Bowden is an American name, but we see this parcel addressed to him:

Perhaps a Besź speaker would assume that David Bowden, the diacritic-less version, is the nominative/vocative. But this parcel is for him, being sent to him, so in Besź you would transform it into the correct case: Dávid Böwdén.

Another big**** change from the book is the spelling of policzai to polizai. I'm going to take this change as a fundamental change to the language: cz doesn't appear anywhere else in our corpus and I'm assuming it was changed because it looked too foreign to an English eye. polizai is just foreign enough while still being somewhat accessible to a native English viewer.

But let's stay on polizai for now. It appears three times in our corpus:

In the first two examples it appears as POLIZAI, without diacritics. Here it's part of a uniform labelling someone as police and a police folder. In the third we have PÖLIZÁI in a line about calling the police. OBVIOUSLY this is another example of the Besź case system; polizai for the nominative, pölizái for the dative or accusative (who are we calling? The police). In the second example (where the word appears on a police folder) this could arguably be the genitive case, as the folder belongs to the police, but I'm going to say that here polizai is acting as a logo rather than a phrase so we'll keep it in the nominative.

We're starting to see a pattern: little or no diacritics for nominative nouns, and more diacritics for nouns in other cases. Because the spelling isn't drastically changing, we can assume that the pronunciation between these words is quite subtle. Foreign characters in the book are often noted as having distinct American etc. accents when speaking Besź, so this nuanced pronunciation is difficult for foreigners to learn. A linguistic feature like this often gets eroded over time and words simplify or change, but Besźel and Ul Qoma are very committed to their distinct cultures so I wouldn't be surprised if this subtle case system was kept mostly out of stubbornness.

Let's look at some other "inconsistent" diacritic use:

There's a lot going on with this one word. Alongside the book's BESŹEL, we have BÉŠZÉL, BÈŠZÈL, and BESZEL. Let's analyse their contexts:

| BESŹEL | [Ŝ]EE BESŹEL, a command: accusative |

| BÉŠZÉL | the name of the city on a map: nominative |

| BÈŠZÈL | W[EL]KÖME TO BÈŠZÈL: perhaps allative? directional? |

| BESZEL | a police patch: genitive? the police belongs to Besźel? |

I'm surprised how well this is working out so far, honestly. We're building a stupid little case system and right now it's holding up.

A note on pronunciation: Besźel is pronounced different ways in the show between actors. Long was allowed to decided on pronunciations and chose [bi 'εi ʒəl], but many of the actors ended up saying ['bεi ʒəl] instead. Long was trying to avoid the adjective Besź sounding like "beige" (X), but alas. That means we have the [bi 'εi ʒəl] camp, the ['bεi ʒəl] camp, and the camp of everyone else in between who weren't quite sure what they were supposed to be saying. Let's chalk it up to differences in neighbourhood dialects.

Let's think about the Cyrillic letters for a moment. In our heart of hearts, we know that the showrunners just threw those letters in to be weird and foreign, but can we analyse their use? Are there any words that appear both with Cyrillic and with Roman letters? Yes! Annoyingly!

- TRAIИING and TRÀINING

- BRÉДCH and BRÉACH

How are we gonna get out of this one, fellas?

The context for TRAIИING and TRÀINING are unfortunately the same: IMMERŠION TRAIИING and TÖURIŠT TRÀINING. Is what an IDIOT would say, because they're obviously completely different. The text that IMMERŠION TRAIИING is part of is cut off, but we can assume the full text is something like [HAVE YOU KOMPLETED] IMMERŠION TRAIИING?, making this not only a question but the object of a sentence - the accusative. On the other hand, TÖURIŠT TRÀINING is a sign, labelling a building, clearly putting it in the nominative. The character И is pronounced [i], giving the word traiиing an extended [i:] sound to contrast tràining; that à clearly breaks up the diphthong present in the English word "training", perhaps giving us a pronunciation more like ['træ i:n i:ŋ]. Wonderful*****.

What about BRÉДCH and BRÉACH? Their contexts again show us they are being used in different cases: ŠPÖTTIИG BRÉДCH IS ÉДSY puts BRÉДCH in the accusative, and TRUŠT IN BRÉACH could be the, um... hang on, I'm perusing the Wikipedia page on grammatical case... let's say the instrumental. We are using Breach to trust. Sure, we'll go for that.

Here's our case chart so far:

| Nom. | Acc. | Dat. | Voc. | Gen. | All. | Instr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borlú | Borlú | Börlu | ||||

| Gadlem | Gadlem | Gádlém | ||||

| Corwi | Corwi | Cörwi | ||||

| Bowden | Bowden | Böwdén | ||||

| polizai | pölizái | pölizái | ||||

| Béšzél | Besźel | Beszel | Bèšzèl | |||

| tràining | traiиing | |||||

| bréдch | bréach |

Finally, I want to note the use of k rather than English hard c:

- Köммuиitч

- ÉXPEKTED

- INŠPÉKTÖR

- KÖMPLETED

- DÖKUM[ENTS]

- KÖMMIŠŠÁR

- KONTROL

- KÖNTRÖL

- W[EL]KÖME

- [DE]KÖRUM

However, this is not consistent and there are several uses of hard c where one would think it might be replaced by k:

- DÖPLIRCAFFĒ

- CÁLL

- Càšé

- UNIFICATIÖN

- FUNICULAR

c is used elsewhere as soft c, in words like Céиter, and I was willing to let that slide as most other [s] sounds are represented with š. Unfortunately, there are still a lot of s characters without the diacritic used (eg. SAFE, VulkövStrašź, MISSING PERSONS), and, most damningly, the spelling of SIGARETTES instead of "cigarettes". What does this mean? Probably that just like English, Besź is a fucking pain in the ass to write for foreigners and you just need to learn the spellings.

With all this in mind, let's put together a complete set of Besź characters.

This bloated alphabet is exactly what we'd expect from Besź so far; it's unnecessarily complicated, with multiple letters representing the same sounds and multiple sounds attached to the same letter. Besź orthography is in serious need of reform, but that's highly likely to be off the table considering Ul Qoma did their own reform and we wouldn't want people thinking we're copying - or worse, trailing behind - Ul Qoma.

Before we wrap up, I want to highlight one more thing. There are very few examples of Group 4, Roman phrases without diacritics. The most blatant case of phrases with absolutely no diacritics is in the Bol Ye'an dig, with the two signs that say "NO UNAUTHORISED ACCESS" and "DANGER NO ADMITTANCE":

There are a lot of foreign students at Bol Ye'an, specifically English-speaking students, so I think it's very fair to say that these texts are not actually in Besź, they actually really are in English. After all, with the cultural context of Ul Qoma being very protective of the dig, there are unlikely to be many Besź natives working there and it would make more sense for these bilingual signs to be in English and Ul Qoman.

Right. Phew. Let's get even crazier with Illitan.

Part 2: Ul Qoma

Illitan is the language of Ul Qoma, and based on the description of the language in the book we know the following:

- Besź and Illitan sound different

- Their grammar, however, is similar and share a common ancestor

- Illitan previously used a cursive, right-to-left calligraphy, and in modern day uses the Roman script

There are a few features of the language that we can see in the book; while ul isn't translated, it features heavily in placenames and even someone's surname (UlHuan). The archaeological digsite, Bol Ye'an, features an apostrophe - maybe a compound word? We see "q" as the representative letter for [k], as in Ul Qoma and the name Qussim. We also see the combination of letters dh, as in the surname Dhatt. We know the Ul Qoman equivalent of policzai is militsya.

- Ul Maidin

- Ul Yir

- Bol Ye'an

- Wahid

- Illya

- Suhash

- Qussim Dhatt

- Aikam Tsueh

- Tairo

- Ul-Huan

- Jaris

People names:

The first thing a language freak will notice about Illitan as it appears in the show is that the script isn't Roman, but Georgian Mkhedruli. Long acknowledges that fans will have turned their nose up at this choice (to be honest I didn't remember that Illitan was meant to be written in the Roman alphabet and was mostly going mental trying to remember what the Georgian script was because I knew I recognised it), and having heard her explanation for this choice I'm on board with it: "This was done because these cities are supposed to exist in this reality. They make references to the United States, they make references to the UK, to Canada, they talk about smugglers travelling over from Bulgaria. [...] So we went with Georgian, which was just different enough that most native English speakers would not know what was going on with it." (X). I think it genuinely makes complete sense for Illitan to use an existing script rather than a brand new one*, especially given where these cities are meant to exist. I'm fine with this choice.

Long's first version of Illitan sounded "too Russian" (she points out that she is a Slavicist, so what did they expect). Although her original brief was for 33 lines of dialogue and a single song translation, she ended up far, far more: "70 street names and 40 area names [unintelligible] city, I came up with band names for posters, menus, brand names for the supermarket, shop fronts, hotel signs, descriptions of artefacts in the museum, and simultaneous translations for the conference meeting between the two sides at the beginning of Episode 1." Long was contacted frequently to come with new words on the spot - she mentions two specific instances when she was attending a football match and was shopping in Marks & Spencers - and the language was in constant flux even when she believed herself finished, as the actors mispronounced, excluded, and added their own Illitan words on the fly (X).

Due to the overwhelming amount of words needed by the show alongside Long's fulltime university work, Long did use shortcuts when she could: "there are places in Ul Qoma which are named after my students, various linguists whose books happened to be on the shelf, favourite footballers..." When called at Marks & Spencers, she was asked to translate the word "wanker" and ended up choosing someone's surname (X).

Thanks to Long's presentation and a couple of other sources, we luckily do have a brief overview of Illitan's grammar and a small collection of vocabulary, including some verb conjugations. Let's look at what we know before we get into the new, written Illitan from the show.

An important note: I will not be analysing any spoken Illitan because it wasn't subtitled in Illitan and I'm not going to bother trying to transcribe a language I don't know and can't double check because it doesn't exist. I value my time (I'm avoiding eye contact with you as I say this).

I will say that I really liked the use of spoken Illitan in the show. The actors sounded very natural for the most part, I liked how authentic the language sounded, and Maria Schrader did a great job making it look like she was casually throwing around words from a language she really knew. Long actually notes that the showrunners "couldn't get hold of me one day for a line they needed and [Schrader] ended up ad-libbing. She got so into the language that she could actually do it and it sounded great."(X) So the sound and use of the language gets an A+ from me!

Illitan grammar & vocabulary

Long explains that originally Illitan had six grammatical genders: animate, inanimate, inanimate-living, abstract, kinship, and learning. She said in her talk that "this was my intended grammar with Illitan originally, and it had 6 genders to start with". It's unclear whether this means the grammar was simplified down the line, but I'm going to proceed as though this structure is still true. There are also no articles (X).

Drawing from Long's knowledge of Slavic language features, Illitan also has three numbers (singular, dual, and plural) and four cases (nominative, genitive, locative, and accusative**). The word order is the same as English to assist the actors with knowing where to place emphasis in their lines (X). Tense and aspect are denoted by infixes (X).

Verbs are for the most part regular. Unlike many other Slavic languages, Illitan prefers to be in present tense and conjugates with prefixes (X). Pronouns appear to be inferred through prefix. In Long's presentation she shows a chart for the present tense conjugation of ahb, the verb "to be":

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dr-ahb | "I am" | fl-ahb | "we (2) are" | stu-ahb | "we (3+) are" |

| tr-ahb | "you are" | gl-ahb | "you (2) are" | sti-ahb | "you (3+) are" |

| sr-ahb | "he/she/it is" | ml-ahb | "they (2) are" | sta-ahb | "they (3+) are" |

The negative is formed with the suffix -na:

- dr-estug, "I know"

dr-estugna, "I don't know"

We have access to an eclectic collection of other vocabulary (X & X):

- Illitan, "English" **

- mihil, "please"

- tikhadme, "thank you"

- vreme, "hello"

- vremelad, "goodbye"

- bezhreme, "sorry"

- dr-izmekhet, "excuse me"

- st-okgrutet dekh..., "my name is..."

- angikt zumkhak Ul Qoma plodir, "make Ul Qoma great again"

- utlok, "to do"

- iquon, "to say"

- estug, "to know"

- buit, "what"

- arkhanan kaliv dekh, "I'm interested in archaeology"

- khet, "fuck"

- gl-ahb apolicz?, "are you police?"

- buit sr-iquon?, "what's he saying?"

- khet sr-estug, "fuck knows"

- sras-oket berdyon, "keep him there"

- Terad Ul Qoma sr-ahb lakhirim kumav res arklimet egaritet, "Western Ul Qoma is particularly rich in our ancient heritage"

Some initial thoughts:

- Due to a mix-up where Long accidentally provided the showrunners with two different words for "please", Illitan now has a familiar/casual "please" and a respectful/formal "please" (X). It's unclear which form mihil is.

- I think arkhanan kaliv dekh, "I'm interested in archaeology", is reflexive - "archaeology interests me".

- This would follow if st-okgrutet dekh..., "my name is...", literally means "you call me..." (either sti- drops the i before certain vowels, or st- marks a different tense thatn sti-).

- In sras-oket berdyon, "keep him there", the conjugation is in the third person singular form. Maybe a transliteration would be "he should stay there" or "he will stay there", with an implied imperative).

- If I'm correct that there is an alternative form of the pronouns for the accusative, then dr-izmekhet, "excuse me", does still have the personal pronoun I in the nominative as though it were the subject of the phrase. izmekhet might then be a verb meaning "to make a mistake" or "to cause a problem".

- When a noun is in the nominative, the pronoun remains: Terad Ul Qoma sr-ahb..., literally "Western Ul Qoma, it is..." But then this makes me question arkhanan kaliv dekh. Surely if kaliv is "interests", this sentence should be arkhanan sr-kaliv dekh? Perhaps kaliv is in a different verb form here, as all other verbs we know seem to start with a vowel to facilitate the pronoun prefixes.

Lastly, I found a page claiming to list the numbers 1-10 in Illitan. I'm not sure what the original source for this was so I'm listing these tentatively (X):

- 1 khab

- 2 kvot

- 3 trost

- 4 fedi

- 5 glil

- 6 grakh

- 7 mlakh

- 8 hatok

- 9 demat

- 10 dekat

That covers everything available online. Let's see if we can learn more about Illitan ourselves.

Illitan corpus

Yeah, yeah, I screenshot as much Illitan as I could find and then transcribed it. Here are my findings.

I'm splitting written Illitan into three groups. I'm not going to tell you what the third group is just yet; for now, please enjoy looking through the first and second groups: translated and untranslated written Illitan. If there's any characters I'm not sure of, I've marked them in orange.

Transcriptions: ☟

- beshel kanhir makhreden, "Besźel border control"

- ul qomame kanhir makhreden, "Ul Qoma border control"

- predbakh omtiritna, "danger no admittance"

- na strakhbaran latkharet, "no unauthorised access"

- gunterstrasv, "GuntérStrašź"

- politsai, "police"

Transcriptions: ☟

- univesitet res ul

- ul maidin dakh-pral

- tik' 964 h

- [...] iqo giganturi sk'ami ola ruse [...]*

- vabyaz

vanyaz - ah

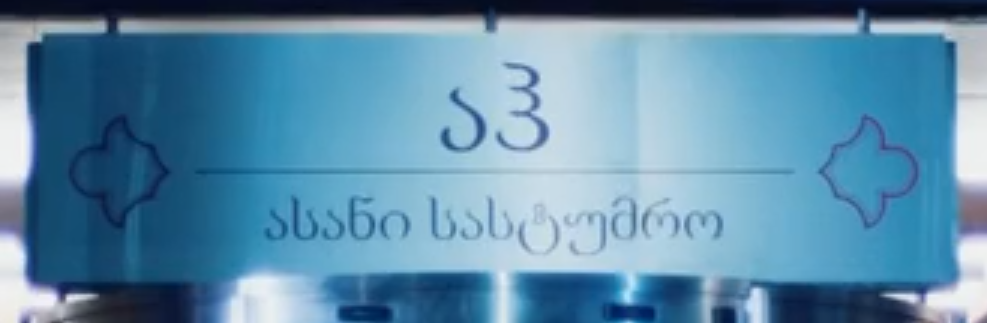

asani sastumro - g?edar kram

- bodinov

- ?igark'an

- aundalia

- revus [...]

- ?a????? omtiritna

- bina 9

- bol ye ' an

ul mabarin pral

ul qoma - n / z / i

- [this text is backwards for some reason] ?ov lp?on

- von si?

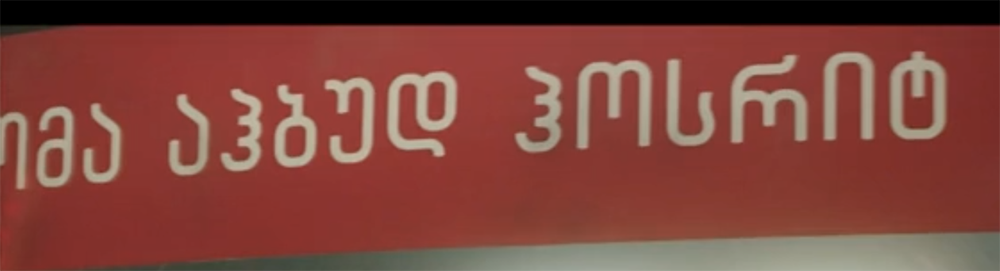

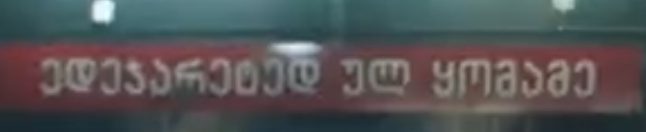

- [ul q]oma ahbud hosrit

- edeyareted ul qomame

- takhi, "taxi"

* Note that this apostrophe is marking [k'] as opposted to [k], which are represented by two different letters in the Georgian alphabet.

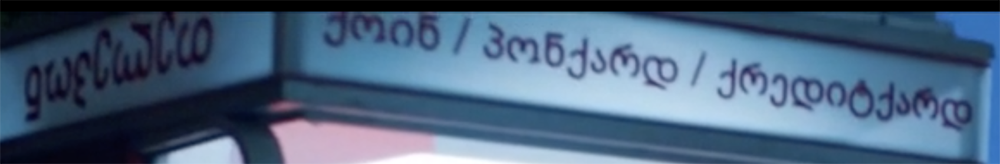

Okay, it's time for Group 3. Here's my grand discovery: a whole bunch of the Illitan in the show is just English written with the Georgian alphabet. Look at this.

Transcriptions: ☟

- artevakt verhous, mo unorthtizd akses, "artefact warehouse, no unauthorised access"

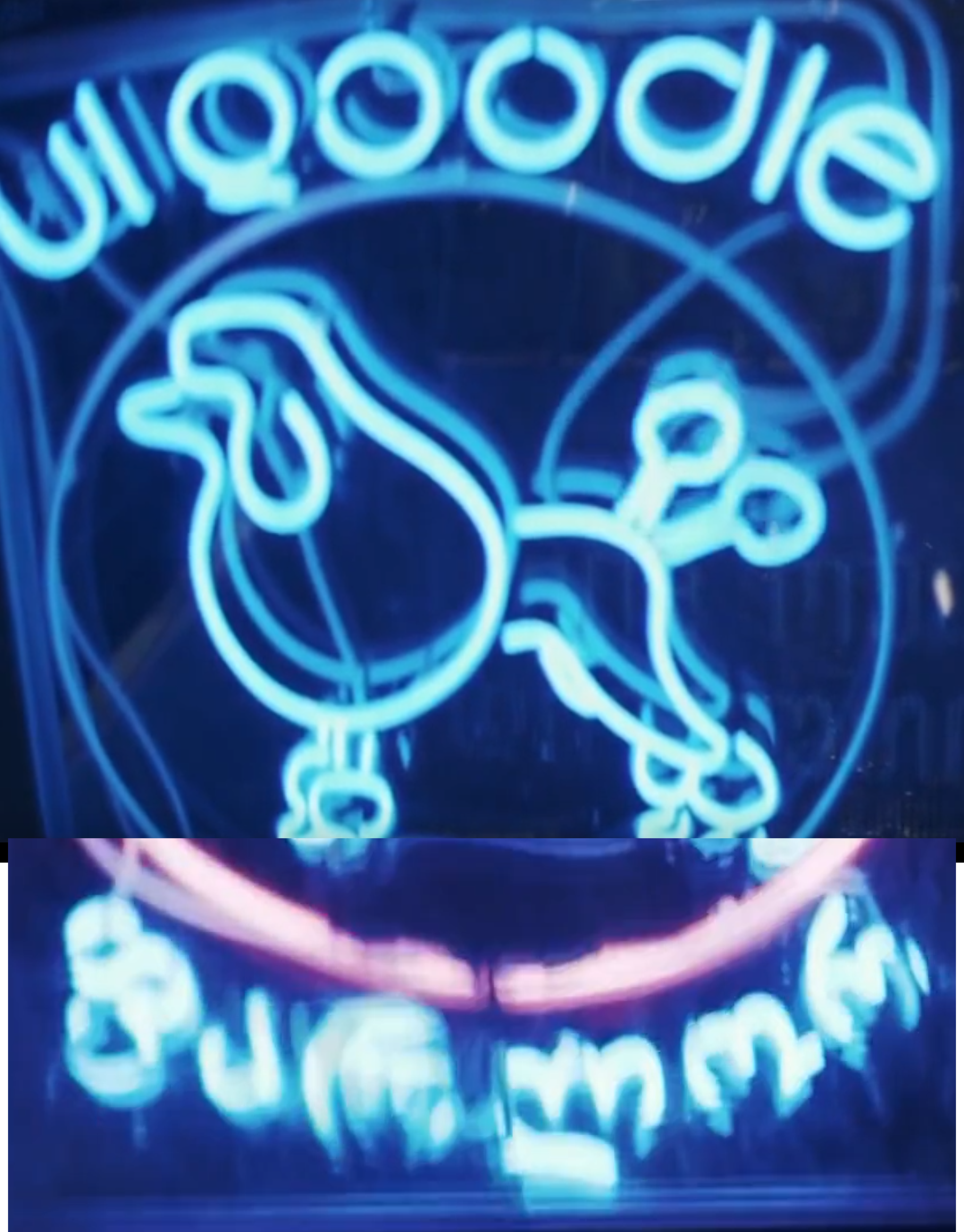

- UlQoodle parlor, UlQoodle "parlor"

- kip out - dizputid zon, "keep out - disputed zone"

- kip out dizputid zon, "keep out disputed zone"

- telepon / koin / ponkard / kreditkard, "telephone / coin / pointcard / credit card"

- klubi / ghame / parti, "club / game / party"

- ven in ul qoma sii ul qoma, "when in Ul Qoma, see Ul Qoma"

- oversight kommittee, "oversight committee" (this one was pointed out by vfig on Bluesky!)

I do think "UlQoodle" rules. I love UlQoodle.

There's a secret Group 4, and that's all the stuff I optimistically screenshot and had absolutely no hope of ever actually transcribing. You are very welcome to shout me (email and social media are in the footer of the page) if you figure out what any of this says!

Illitan analysis

Let me tell you... realising that there was a good amount of text in the show that was basically English sucked. After listening to Long's presentation and hearing how much she translated, I was expecting sooo much background detail. But what likely happened was that she was on call for translating dialogue and assisted with some important background translations, but the art departments didn't want to ring her up every time they needed a word like "coin" or "taxi" when they already had the alphabet on hand. They could just slap that stuff together, and slap they did. Long made this point in her talk: "My impression is that people, when they say "we need a conlang", they don't really understand what's involved. They also don't understand how much of it they're going to need. So when they said, "oh, we've got this dialogue, oh, he says it in Illitan, can you just 'translate' that for us?" - you mean 'create' that for you, okay." (X) There's always more that needs to be designed than expected.

I also noticed that whoever put this telephone booth together put the word "telephone" in upside down lmao:

That's not to say there isn't some interesting stuff to look at. Let's start with Group 1, the translated texts. To my surprise the word emblazoned on the Ul Qoman militsya's chests wasn't militsya... it was politsai, the same as the Besź word (polizai). Considering militsya is one of the very few Illitan words we get in the book, I'm not sure why this was changed - I like that the two cities have different approaches to law enforcement and this was reflected in this different vocabulary. One of the words we got in our canon list of vocabulary directly from Long is apolicz, in the context of gl-ahb apolicz?, "are you the police?". In this position, the prefix a- might indicate the accusative case. I'm probably getting bogged down in the weeds here. It doesn't matter that much***.

We learned a lot of new info and vocab from Group 1:

- beshel, "Besźel"

- In ul qomame kanhir makhreden, "Ul Qoma border control", the word ul qomame is in some kind of case form. beshel is not in this form even though it appears in the same context (beshel kanhir makhreden).

- predbakh, "danger"

- omtiritna, "no admittance", using the -na negative suffix

- However... na strakhbaran latkharet, "no unauthorised access", has an entirely different negative structure for some reason

- gunterstrasv, "GuntérStrašź", even though Illitan does have a z letter - perhaps it isn't actually pronounced [z]

Even though we don't have the exact translations written out in English/Besź, we can still deduce the following from Group 2:

- universitet, "university" in an unknown case. The full line that unversitet appears in is universitet res ul, which is translated on the item as "University of Ul Qoma". Obviously we don't see the word "Ul Qoma" on the package, and "Qoma" was probably excluded for space reasons (they probably set the text, saw that it would be too long, and were like ah fuck it remove that last word) but I'm approaching this as if everything presented is intended. It doesn't make sense for "university" to be in the genitive case here - it's not the university's Ul Qoma, it's Ul Qoma's university - so maybe posessives are constructed differently. We know that there are no articles in Illitan so res ul can't mean "of the" (where I'd be assuming ul means "the"). ul must therefore be accepted shorthand for ul qoma, formal enough in construction to be permitted to be used to label important university possessions, and somehow universitet res ul really does translate to "University of Ul Qoma".

- dakh-pral, "avenue". The presence of a hyphen suggests this is a compound word; I assumed apostrophes were how compounds were made, and they're famously the best sign of a novice conlanger****. The only example of Illitan with an apostrophe in the middle is Bol Ye'an, the name of the archaeological dig. I was wondering if they were just going to forgo any apostrophes entirely but no, on the address to David Bowden we see that there's an apostrophe in there. Odd! So since it's dakh-pral and not dakh'pral, I guess either this isn't a compound or Bol Ye'an isn't a compound :(

- asani sastumro, the name of a hotel - I did go back and check the episode because I remember a character saying the name of the hotel, and the line is "No smoking on the azian's premises". Is asani the word for "hotel" or the name of the hotel, and is it a different case of the word/name asian/azian? Much to think about.

- bina, "room" or "flat"

- These two signs are the equivalent of the Besź signs we see in Copula Hall:

[ul q]oma ahbud hosrit | edeyareted ul qomame

We can see that edeyareted ul qomame has "Ul Qoma" in the same case as in ul qomame kanhir makhreden, "Ul Qoma border control". It could be the nominative, but since we see ul qoma without any suffixes elsewhere I think -me indicates the locative case; "at Ul Qoma border control", "welcome at Ul Qoma". That means [ul q]oma ahbud hosrit must mean something about leaving Ul Qoma; if we follow our assumption that verbs often begin with vowels, ahbud may be a verb to do with leaving. In French, "I miss you" is literally translated as "you miss me" (tu me manques), swapping the object and subject, so maybe that's a similar thing that's going on here. - takhi, "taxi". I'm letting this one slide - it's not unusual to see English words adopted into other languages as technology develops.

- For the same reason, even though they're in Group 3, I'm accepting telepon, koin, ponkard, kreditkard, klubi, ghame, and parti as legitimate Illitan words. pointokaado is literally the Japanese word for "point card", how can I refuse the same for Illitan?

Let's review what we knew about Illitan at the start of this journey. I hypothesised that the apostrophe in Bol Ye'an indicated a compound word and this may still be true, but we've seen no evidence in our limited samples. "dh", as in the name Dhatt, does not seem to appear anywhere in our written samples; however this is due to the fact that Georgian has no "dh" letter, and we can assume that some of the "d" appearances in our texts above may actually be transcribed as "dh". Lastly, in the book "q" was suggested to be the representative letter for [k], but I did also just notice that the name Aikam features a "k" and our samples include the Georgian letters for [k] and [k']. That means there are three different [k]-adjacent sounds in Illitan, each with their own letter, and like the Besź case system this has probably stuck around for so long because of the cultural divide between the two cities. Not even the reform of 1923 could smooth this one over.

With that out of the way, we can finally put together a complete set of Illitan characters.

a

b

g

dh

e

v

z

t

i

k'

l

m

n

o

r

s

t

u

p

k

q

kh

*

*y

h

* This character appears as ჯ in unicode and I thought I was going nuts, like did they invent a new letter just for "y"? Am I insane? I could see it on one image on the Wikipedia page for the Georgian Mkhedruli alphabet but could not figure out what was going on, and eventually I used Shapecatcher to find and screenshot it. You're welcome.

Part 3: Orciny

The space between... fitting into neither Besźel nor Ul Qoma... it's all the other stuff I wanted to mention but didn't have a place for.

In the book, areas where the cities get dangerously close to mixing are called "crosshatched". If two locations are near each other they're "grosstopical", and if there's a location that exists in the same location as a street in the other city they're called "topolgangers". That rules.

The two cities are opposing factions and the only way to legally cross from one to the other is through Copula Hall; entering through one end and exiting the other places you on international grounds, even if you're standing on the exact same street you were on just moments ago. In linguistics, a "copula" is a connecting word, usually a verb, used to join a subject and predicate. The copula in English is "to be": I am thirsty, she is tall. It comes from the from Latin copula, meaning "that which binds, rope, band, bond" (X). This is a really fun name for a location that literally acts as a link between the cities, and has the double meaning not only of linking but also equating - the city is the city. Besźel is Ul Qoma. Ul Qoma is Besźel. Great name to tie into themes this book had no intention of exploring in an interesting way.

"Copula" is pronounced COP-you-luh. In the show, they pronounce it like cuh-PAW-luh and brother, I hated it. My friend (yes I told the group chat about this) pointed out this was probably to avoid people being like "lmao what?? copulate hall???" and I massaged my very big brain and was like "well yes but they share a root, you see, so yes, it is copulate hall". Anyway, that's that on that.

Check out this garbage truck.

An Illitan slur for Besź people is (as far as I can make out) byetut, "crow/scavenger" (Episode 2). It comes from the fact that Besź will cross the border to scavenge material from Ul Qoman rubbish tips, which they can then bring back to sell in Besźel. The fact that this concept was taken to be the literal representation of the Ul Qoman refuse management company is very funny.

I like the logo for the show a lot, and I like getting to see the map before and after Ul Qoma is blocked out. It's just fun.

That's all I got for you! :) Bye!

References:

- The City & the City by Miéville, published by Pan Books (2009)

- The City and the City adapted by Tony Grisoni, Mammoth Screen (2018)

- "Ul Qoma pulls an Ataturk and Switched to Roman Script, Not Bastardized Georgian: Creating a Language for The City and the City", presented by Dr Alison Long at the 8th Language Creation Conference, 2019 (transcription here)

- Dr Alison Long (Linguist) - media pack for The City & the City, BBC

- How I invented a new language for The City and The City - Dr Alison Long, The Conversation

- Counting in Illitan - Of Languages and Numbers

- "Copula" - Etymonline

- Shapecatcher

- Not really a reference, but I found this website called Lexilogos with all sorts of dictionaries and keyboards