Transcript of "Ul Qoma pulls an Ataturk and Switched to Roman Script, Not Bastardized Georgian: Creating a Language for The City and the City"

This is a transcript of Dr Alison Long's presentation for the 9th Language Creation Conference, hosted by the Language Creation Society, streamed June 23rd 2019. Her talk covered her conlang work on The City and the City, a BBC adaptation of the China Miéville novel of the same name. This isn't a full transcription - I left out a very small section near the beginning that wasn't entirely relevant to the topic, as well as some points where Long was reading out exactly what was seen on the slides - and there may be some misheard sections. I transcribed this for my own use when writing up my overview of the languages in The City and the City and figured I would put it here in case anyone else was interested in the full presentation but was unable to understand the poor audio in the recording.

You can listen to the recording in full here (it starts at 2:51:44).

Transcript

This was actually my first real attempt at a conlang, constructed language. I had one when I was a child - I had very bad asthma as a child, so often I was having a bad time and couldn't speak, so I had this kind of wheezing, tapping language that only my family could understand, until my father taught me morse code and then I started doing [unintelligible]. So that's probably a prototype, maybe.

So really, I don't have the [unintelligible] for world-building, so the things I've been hearing here are absolutely phenomenal. I can't do that, I just can't, I know I can't, so I take other people's worlds and I sort out the languages for them. Hopefully. [...]

[Quoting from The City and the City] "In the Land of Alphabets Arabic caught Dame Sanskrit's eye (drunk he was despite Muhamed's injunctions, else her age would have dissuaded). Nine months later a disowned child was put out. The feral babe is Illitan, Hermes-Aphrodite not without beauty. He has something of both his parents in his form, but the voice of those who raised him - the birds." This is quite a big ask if you're trying to put a language together.

So what we also know from the book is that Illitan lost its original, right-to-left script "overnight" in 1923, and this is brings us back to the title. Somebody on Twitter took exception to the fact that I'd used the Georgian alphabet for Illitan when in the book it's the Latin/Roman alphabet, and told me off for just Illitan into bastardised Georgian... it's not. It uses the same alphabet, although some of the letters do not exactly correspond to Georgian, and this was done because these cities are supposed to exist in this reality. They make references to the United States, they make references to the UK, to Canada, they talk about smugglers travelling over from Bulgaria. So we know these cities are supposed to exist somewhere probably along that sea coast, somewhere between Bulgaria and Turkey. So as part of that, I did create an alphabet to start with, but noticed too many technical issues with creating a font for it, for the computers, for a start. So we went with Georgian, which was just different enough that most native English speakers would not know what was going on with it. And that's what we're working for.

Just something about the pronunciation of Besź [bi 'εi ʒəl], I was allowed to decide on pronunciations, so I said [bi 'εi ʒəl], but a lot of the actors called it ['bεi ʒəl]. The problem with ['bεi ʒəl] is that the adjective becomes "beige", so you have "beige" people and "beige" food.

So we had a few differences in the adaptation because of course you cannot just translate directly from a novel to the screen, it just doesn't work. [...]

[...] and of course we had to change the languages. Now Besź - again, I got into trouble for this and I apologise to any Slavicists in the room - we had to use fairly random-looking diacritics, we had to use what people think is the backwards R, the backwards N, which we all know is "ya" and "i" if you're a Slavicist... that wasn't my decision, but native English speakers (and that's the majority of the BBC audience) needed to be able to understand what was all written in Besźel. I did give them what I thought was reasonable Cyrillic that they said "nobody's going to understand that unless they've got a phD", and I said "fine, okay". So they know better than I do, what works on TV, so I left them to it.

So as we said, Besź: Roman script, some diacritics, occasional Cyrillic letters which weren't being used as we know they would be (although my argument here is that there's something that looks like a "P" in Russian that's actually an "R", and you can get this in different languages... this is very revisionist at this point).

Illitan had to look and sound completely different. The first attempt I made at this came back and they said, "that sounds too Russian", and I thought "okay, why did you come to a Slavicist to do this if you didn't want something [drowned out by laughter]". So I had a small tantrum in my office and then I set about it, and at this point I started making random noises to myself. So using the Georgian script, this is what "Ul Qoma" looks like. It's literally just transliterated, more or less.

My original brief, and I'm quoting here: "We just need 33 lines of dialogue and a song translation." Okay. I did those 33 lines and a song translation, did a further 3 song translations, I did background dialogue, I came up with 70 street names and 40 area names [unintelligible] city, I came up with band names for posters, menus, brand names for the supermarket, shop fronts, hotel signs, descriptions of artefacts in the museum, and simultaneous translations for the conference meeting between the two sides at the beginning of Episode 1. My impression is that people, when they say "we need a conlang", they don't really understand what's involved. They also don't understand how much of it they're going to need. So when they said, "oh, we've got this dialogue, oh, he says it in Illitan, can you just 'translate' that for us?" - you mean 'create' that for you, okay - but they've never worked with [unintelligible], so there's a lot of give and take on both sides, there has to be. But it was a huge undertaking, and I was doing this at the same time as working fulltime at university. So when they came to me and they said, "we need 70 street names and 40 area names for both cities," I was in my office, I said, "Okay, when do you need these for?", thinking, you know, a couple days or something. "Oh, we need them for 9 o'clock tomorrow morning because we've got [unintelligible]." ...Okay! Okay, so I sit in my office and I'm looking around my office, so there are places in Ul Qoma which are named after my students, various linguists whose books happened to be on the shelf, favourite footballers, but they all sound suitable Illitan, so you wouldn't...

And this is another issue here: the scripts change regularly, they always do, they need stuff they didn't realise in the first place they needed. I was only actually on set for four days, so the rest of the time I'd be getting phonecalls at odd hours, one of which came when I was watching a football match at a quarter past 9 one evening (at ground - how they got signal I don't know, because I can never get signal). And they said, "We need a phrase!" and I said, "Well, can it wait? Because I'm tied up here-" "No, no, we need it now." "Right, okay, what's the phrase you need?" And they told me, so I had to get up, go down to the lady's loo, all the while I'm trying to think up this phrase - I didn't have any of my stuff with me - go to the lady's, text it to them, make a voice recording, send that as well. And then when I got home and I looked up what I'd sent I realised that I now had two words for "please" in Illitan because I couldn't remember the original. So again, being revisionist, we have two words for "please" in Illitan: one is a familiar one that you use with equals or with children, and the other is one that is a respectful one that you use to elders or... does that work? I'm asking you guys because you're the experts. I'm making this up as I go along.

They phoned me and asked me for an insult word while I was doing my shopping at Marks & Spencers. Marks & Spencers is a rather gentile British store, and there's a very British insult word that rhymes with "banker". And I'm standing in Marks & Spencers, "I can't say a word like that in Marks & Spencers!", and again, you know, had stuff with me, I'm looking around the shop thinking "what could I possibly..." And then I remembered someone who'd aggravated me quite a lot so that person's surname has become that word in Illitan. Please don't tell.

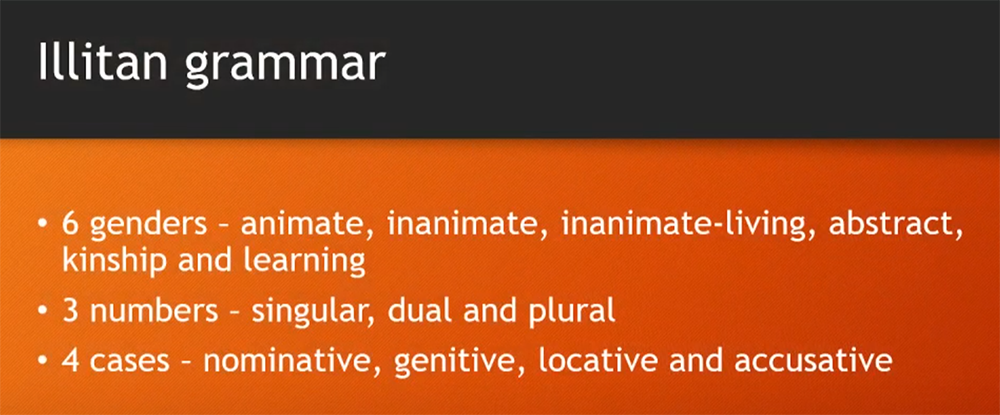

So this was my intended grammar with Illitan originally, and it had 6 genders to start with and this was purely because I was having an argument with somebody at work about the nature of grammatical gender and I wanted to wind her up (and I'm also a morphologist so I love playing with this kind of stuff anyway.

Three numbers - now this is an old Slavic thing as well which still exists in in Slovene, so we have singular, dual or plural, because I was determined to get some Slavic influence in there somewhere. And 4 cases, nominative, genitive, locative and accusative. And that's how it started. I also took out the articles because that's again another very Slavic thing to do, and it saved me some time.

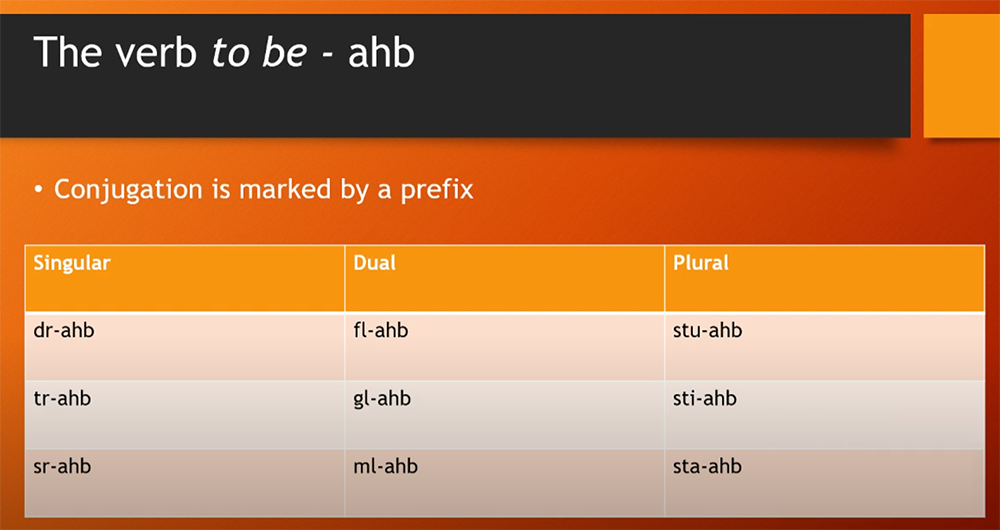

We do prefer to be in the present tense in Illitan, which in many Slavic languages you don't. So conjugations are marked by a prefix. [...]

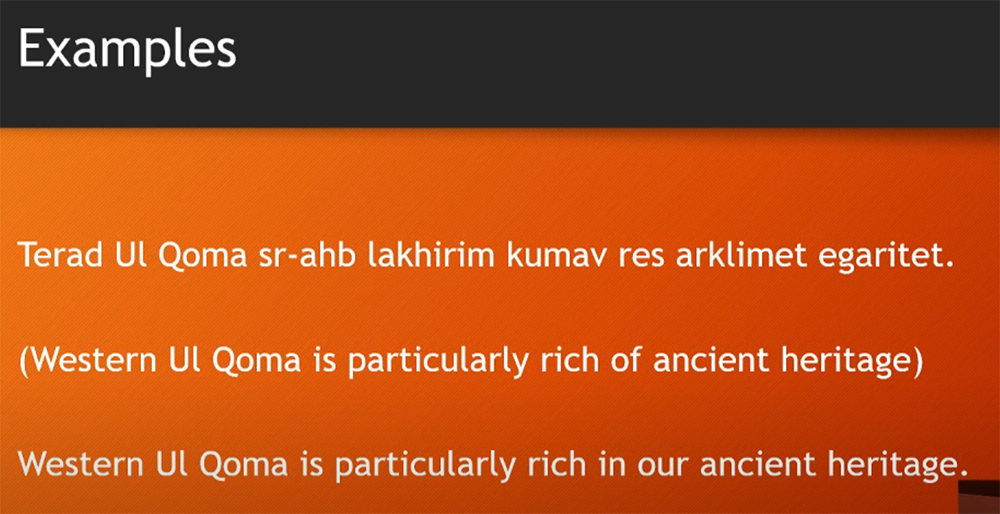

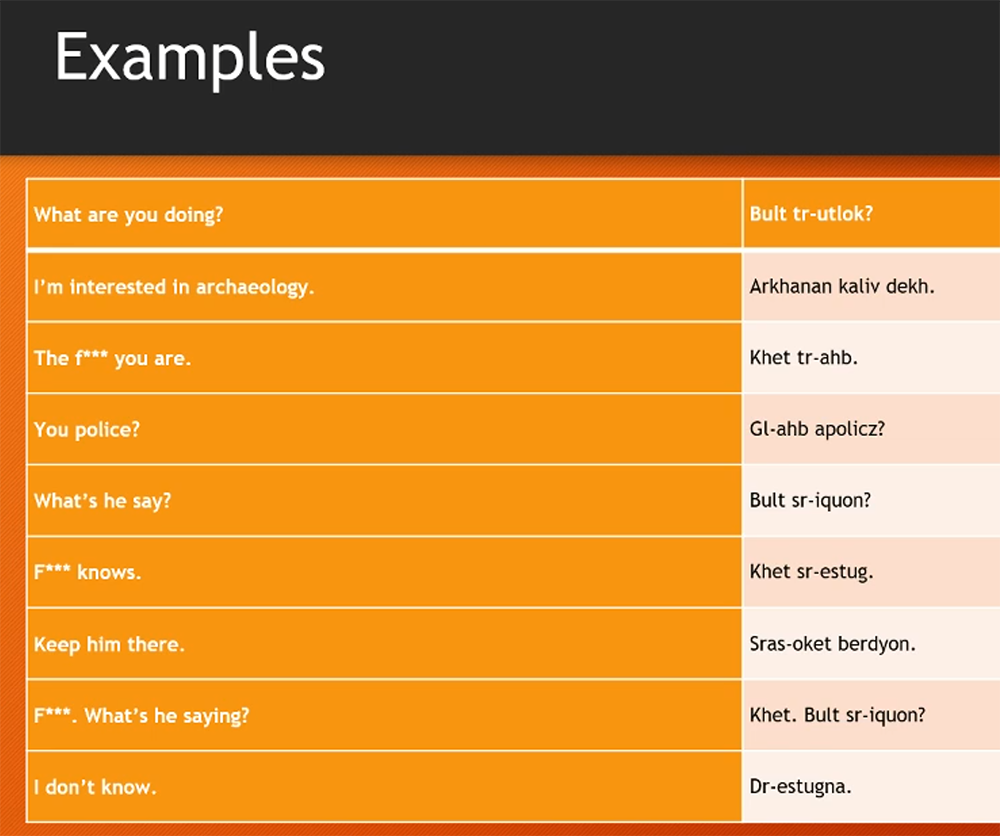

So some examples from Illitan - this is the first line in Illitan that's spoken in the series, and I should point out I kept the English word order because all the actors, even though we had a lot from Eastern Europe, they were all fluent English speakers, so I kept the word order just so they knew roughly what they were saying at which point so they knew where emphasis should be and everything.

That's a stunning line to start with for your language.

So Gary's talk yesterday [The Benefits of Proto-Conlangs], talking about making languages sound more real as well - I find if you give the script to actors, that helps. There was a Czech actor who was playing a policeman in it and he came to me with the script and he said to me, "which language is this?" and I said, "I created it", and he said, "so it's fantasy", you know, that very Slavic way, cut to the chase. And I just said, "well, yes," and he said, "it's too long," and cut about 90% of what I'd written for him. And I bit my tongue very hard. The way he did it though, it was perfect, and I figured it was very collaborative process from that point because they know what they're doing on screen. They know what works. I don't. I know what works with the language, and if I have to then go back and be a bit revisionist about it, okay, right, okay, how do we make this work now, fine. But they were the guys in front of the cameras, so I had to let them use as best they could[?].

Something else, Maria Schrader, who was in Deutschland 83 if any of you are familiar with that...? She played an Illitan speaker; they couldn't get hold of me one day for a line they needed and she ended up ad-libbing. She got so into the language that she could actually do it and it sounded great, but that did mean when I came to do the subtitling I then had to add her words to my lexicon, and I should really give her credit for that.

These are the first lines they wanted me to create.

Now of course, that particular word in English can be used in a number of different ways: as an adjective, a verb, a noun. It's just the one word in Illitan.

Now I haven't done proper phonetic transcription because if you give that to actors they cry, so I'm just showing you what I gave to them. So this is basically when the lead character is being beaten up in a tunnel somewhere and they're trying to find out what was going on. The other thing that happened while they were filming this was that the director said to me, "could you just give those two sort of half a dozen lines to say to each other while this is going on?" ...Okay then! And of course my brain froze, but one of the actors was a Maltese speaker which means that the word for "work" in Illitan, which of course I can't remember, is actually based on the Maltese word for "work", so we have different influences. A lot of borrowings - again, I was trying to make it a messy language but when you try to make something messy it becomes uniformly messy, so quite a lot of the mess has come from the fact that they were phoning me at odd hours and asking me for phrases when I didn't have my stuff with me. And also from the actors not being able to pronounce what I'd given them. And at that point you just say, "oh, it's irregular, that's fine, we'll say that."

That's the Golden rule: as long as the actors can actually say, physically, what you've given them to say, and make it sound like it means something which it often did. When I was recording stuff for them it was very flat, I was talking to myself an awful lot, but as soon as the actors got hold of it they made it sound really, really good, so I'm very grateful to them because they made it live, really, whereas I was just sitting in my office using people's names for places and things like that.