Continuing my efforts to archive my work, here's an essay I wrote for my comics masters in 2018!

Autobiography as a literary genre has a long-standing history but it is only recently that autobiographical comics have been brought into the spotlight. Unlike other other mediums, autobiographical comics are able to construct narratives about identity in a way that is unique to the visual medium by separating the artist self from the character self from the narrative self. The reader is aware that the character and the creator are not the one and the same, that the character depicted on the page is a representation of the author rather than a direct replica, and this juxtaposition and also separation allows the author to more fully explore their identity. Most autobiographical work, however, is constructed long after the depicted events have transpired and with the benefit of hindsight, allowing the creator to piece together a narrative and select particular aspects of one’s identity to focus on. Hourly Comic Day, a global event where artists draw a comic about each hour that they are awake, both challenges and confirms these conventions of autobiography though the nature of the comics’ production. By comparing different artists’ hourly comics, one can determine that representations of the self can be used in different ways to more deeply convey one’s identity or create a degree of separation between reader and artist*.

Through analysis of autobiography, scholars have discussed the emphasis of narration in the genre and how this narration relates to our construction of our identity; we create autobiographical narratives in order to “make sense of our identities and the social spheres in which we exist” (Jacobs 2008:70). In other words, the self is given a context within which one can explore aspects of one’s identity. Autobiography is also naturally reliant on memory and, as such, is susceptible to its narration being a reconstruction rather than true delineation of facts. This reliance shapes the narration: “our remembered experiences are continuously reinterpreted in the light of what, with hindsight, is seen to be significant […] The artist’s retrospective body image will inevitably be shaped by the way he currently feels about his physical self, both past and present” (El Refaei 2012:59). By looking back on past events with the knowledge one holds in the future, one can pinpoint moments or memories that have greater significance to the apparent narrative of one’s identity than they did at the time.

An example of this would be Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, an exploration of Bechdel’s burgeoning queer identity growing up and its correlation with her father’s closeted homosexuality. In creating her story, Bechdel may have made connections or placed greater significance on moments that link with the narrative she seeks to present than she would have at the time. Furthermore, where mediums such as photography are able to capture moments exactly, regardless of whether or not the artist remembered specific details, “the illustrator […] is forced to act on memory and interpretation” (Millan 2012:33). The artist’s own interpretation is then reinterpreted by the reader, who takes what is presented as the truth of that moment. Therefore, an autobiography can manipulate the presented truth depending on what details or what aspects of one’s self one chooses to depict.

Some argue that autobiography, being a “consciously constructed narrative”, presents the autobiographer “as he believes and wishes himself to be and to have been” (Jacobs 2008:70), but this is not always the case. Some autobiographical comics, particularly those out of the mainstream, depict unflattering and demeaning versions of the self, as is investigated by Dale Jacobs in his analytical essay on Joe Matt’s Peepshow: “Peepshow presents a narrative self-portrayal that is anything but flattering, as Joe Matt lurches from one embarrassing situation and demeaning piece of self-disclosure to another” (Jacobs 2008:71). Accurately representing and examining the self is the theme of many autobiographical comics and so it is no surprise that the context in which one discusses one’s identity or identities is often a negative or difficult angle. Philosopher Drew Leder discussed the body as characterised by absence and how one is only conscious of one’s body when it is no longer in “a desired or ordinary state, and as an alien force threatening the self” (El Refaie 2012:57). As a result, when constructing an autobiographical narrative, one depicts one’s self in a context, usually where one is at odds with the surrounding narrative: Bechdel’s open queer self with her father’s closeted one; David Small’s voiceless and violated self with his parents’ stubborn silence in Stitches: A Graphic Memoir. The autobiographer naturally seeks out these identity-supporting structures and makes use of them to construct an overarching, continuous narrative that supports one’s sense of identity (El Refaie 2012:58).

The comics medium is particularly capable of achieving this. The act of simplifying an image for a comic is a conscious choice to amplify certain elements, as Scott McCloud explains: “When we abstract an image through cartooning, we’re not so much eliminating details as we are focusing on specific details” (McCloud 1994:30). By drawing one’s body in a certain way, one draws attention to certain aspects of and indicates the artist’s perception of one’s identity, such as Small’s relatively simple depictions of himself versus the detailed way in which he draws his scar, indicating his upset at this violation of his body (Small 2009:165). One’s body fits many socio-cultural contexts at once, however – “a woman’s body, a Latina’s body, a mother’s body, a daughter’s body, a friend’s body, an attractive body, an ageing body, a Jewish body. Moreover, these images of the body are not discrete but form a series of overlapping identity whereby one or more aspects of that body appear to be especially salient at any given point in time” (Weiss 1999:1).Far from being constrained to depicting one self at a time, autobiographical comics can take advantage of the medium to depict a multitude of selves concurrently.

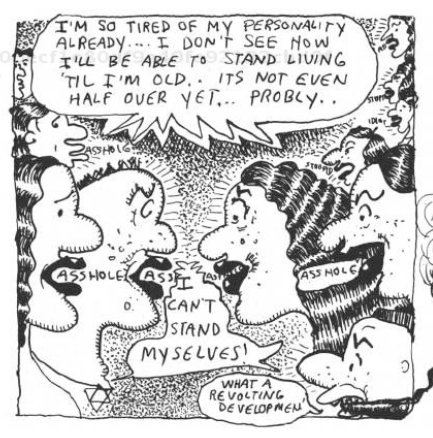

Cartoonist Aline Kominsky-Crumb does this quite deliberately by drawing herself drastically different from panel to panel, as is outlined by Hillary Chute: “Aline’s clothes might suddenly change; bodies tend to swell and shrink. Kominsky-Crumb’s noncontinuous self-representation […] unsettles selfsame subjectivity, presenting an unfixed, nonunitary, resolutely shifting female self” (Chute 2010:31). Kominsky-Crumb goes so far as to bring her various selves to the reader’s direct attention in Up in the Air in a panel where her various selves face each other and simultaneously shout “I can’t stand myselves!” (Kominsky-Crumb 2000:63) Kominsky-Crumb’s goal isn’t physical accuracy but accuracy to her self-perception. Rather than choosing one identity around which to construct a narrative, she lets the reader look at all of her selves, even though some aspects of her self-identity may not be appealing.

Accuracy to the “truth” is a constant source of friction in autobiographical work. The reader must place their trust in the author that what they are reading is at least parallel to the truth. Artists such as Kominsky-Crumb rely more heavily on “a realism of quality and feeling if not a visually mimetic realism” (Chute 2010:48-49), where even if the events depicted are not precisely true to life, the emotions she tries to invoke are closer to how she perceived the event. This is often heightened by her mode of writing, which is not “correct” English and often forgoes grammar in order to be more expressive (Chute 2010:35). The same idea can be found in Small’s depiction of his scar in Stitches; as well as drawing attention to that facet of his identity, the detailed way in which he draws his scar isn’t necessarily true to life but rather true to his perception of it at the time. In autobiographical comics, then, depictions of the self may not necessarily be visually accurate but will often be accurate depictions of the artist’s mental or emotional state at that time.

With this in mind, let's take a closer look at hourly comics and how these overarching elements of autobiographical comics are adapted to the very specific criteria under which hourly comics are made. Hourly Comic Day is an event inspired by cartoonist John Campbell, who began drawing small comics detailing what he did every hour that he was awake. It became a worldwide event, taking place on February 1st every year from 2006 onwards, and today comics artists of all kinds join in. As it is an informal event, the “rules” are loose; some artists draw their comics every hour, some draw them at the end of the day or after the fact, some start and don’t manage to finish. What makes hourly comics (or “hourlies”) interesting, however, is that they deal with almost every aspect of autobiographical comics discussed in this paper so far. Autobiographical comics inherently look back on an event and retroactively seek out narrative threads; as many artists draw hourlies throughout the day, significance needs to be created from seemingly unimportant or unobtrusive events. Artists scrutinise and depict occurrences simply because they were the defining moment of that hour. Events can be said to be more “truthful” as they are not distorted by time passing and even the mundane is given a spotlight. Which self the artist chooses to depict affects the tone of the comic; some artists choose to draw their trip to the shops or their phone call to the bank, while others detail their mental state and philosophise over their existence, but whichever self is presented can be said to be a clear picture of one aspect of the artist’s self-identity at that moment in time. Due to the time constraint of having to push out a comic an hour as well as continuing to go about one’s day, the artist does not normally have time to plan and draft layouts or panels to more completely convey the event – it may be interesting to argue that this is perhaps a more honest approach to autobiographical work, on-the-fly diary-keeping rather than narrative reinterpreted through hindsight. Furthermore, as Jacobs stated in his analysis of Peepshow, ongoing autobiographical work means that “experiences become narrative, which then has an impact on future experience and subsequent narrative” (Jacobs 2008:72). This is often the case with hourlies, where the act of drawing the comic one hour may become part of the narrative and be continually self-referenced throughout the comics, or the focus on a seemingly insignificant event one hour may influence what the artist chooses to focus on later in the day. Due to the widespread variety of artists who participate in Hourly Comic Day and the limitations of this paper, it is impossible to look at more than a few examples, but those that have been selected make use of representations of the self in different and interesting ways.

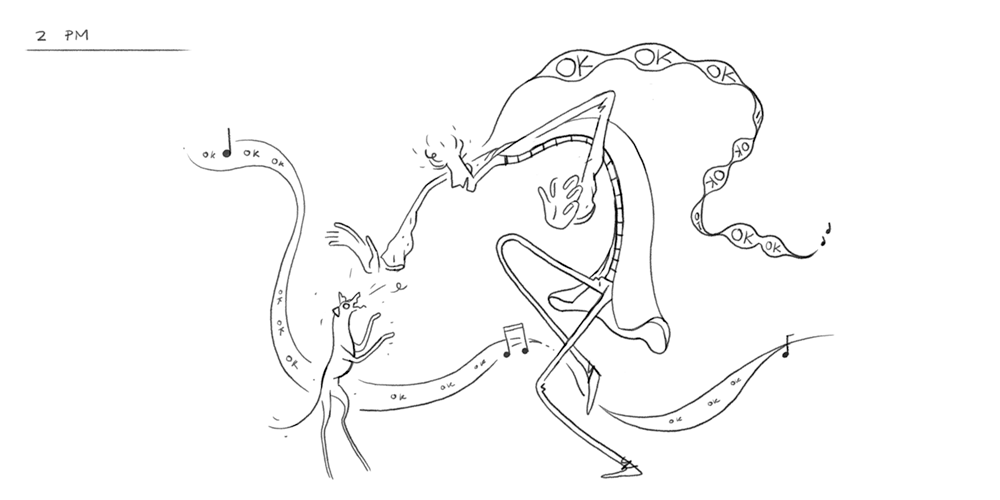

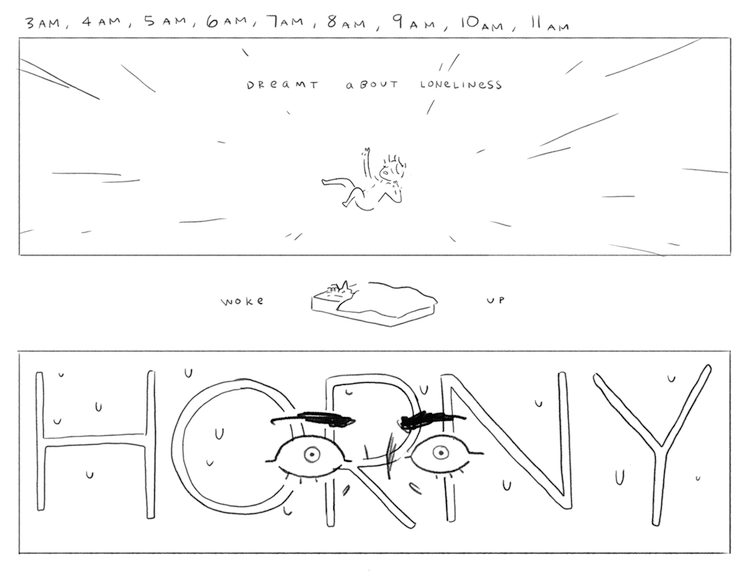

The first artist whose hourlies will be looked at is Cole Ott, an illustrator and animator from New York. His regular work is highlighted by his bright colours and use of distorted and expressive yet simple forms and his hourlies (Ott 2018) regularly make use of exaggerated imagery in order to make otherwise boring events interesting. Many panels forgo explicit narration and even borders, as in his 2pm strip.

Ott makes use of sparse lines and exaggerated features in order to highlight the most important parts of himself and more accurately represent his emotions at any given moment – the few features that do carry from depiction to depiction are his hair and nose. He is also often the focus of panels, his representative self being the only thing we see in a blank void, as above, although there may occasionally be the suggestion of backgrounds, as below. Rather than wasting time drawing the entirety of himself, Ott often abstracts his form, such as in his 2am strip, where the simple act of having a midnight snack becomes “scavenging”, his eyes and figure distorted into monstrous proportions, not a physically accurate self but an emotionally true self.

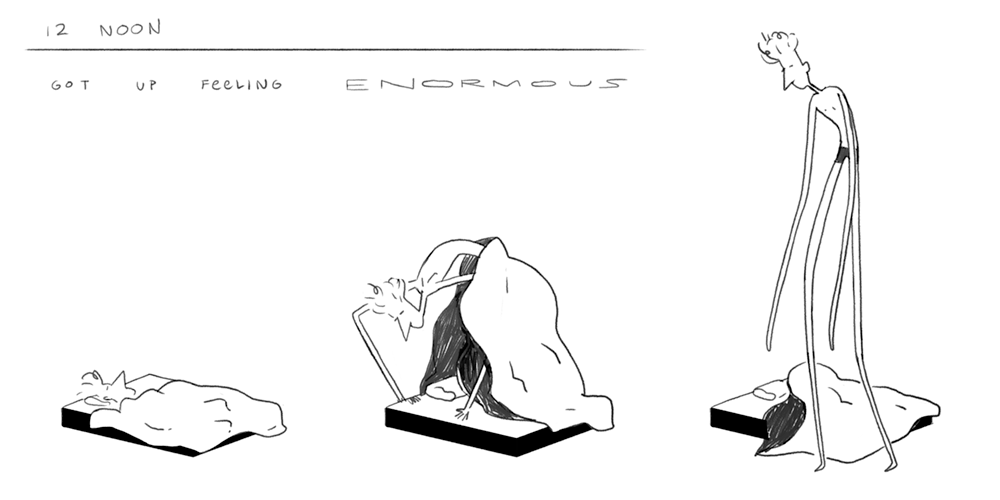

Text and panels also become an extension of Ott’s depicted self, as in his 3-11am and 12am strips. Words stretch and expand to mimic their meaning: “horny” fills the panel, which acts as a representation of Ott, his disembodied eyes staring out at us and sweat dripping down the panel itself; “enormous” elongates just like Ott emerging from his bed, his limbs grown long overnight. This stretched-out version of himself carries throughout the comics until the 5pm strip, when he takes a nap that presumably calms this perception of himself.

Ott not only depicts the events that happen but lets us in to his occasional thoughts throughout the day: “I want to be a better gift-giver this year” or “I love when ppl [sic] draw themselves naked in their hourlies!!!”. Ott completed his hourlies throughout the day, and while there is no overarching narrative as one would find in a regular autobiographical work, he shares an honest overview of his day and is direct about his emotional state.

The second artist is Joe Sparrow, also an illustrator and animator, from London. Sparrow’s regular work uses very clean, geometric shapes to convey intense emotion. Unlike Ott, Sparrow’s hourlies (Sparrow 2018(1)) are more regular in format; each strip is comprised of four hand-drawn panels and his depiction of himself stays constant throughout, a very simplified cartoon character whose glasses warp to emote like eyes. He often draws complete but stylised environments, such as drawing his entire bedroom in his 10pm strip as he lies facedown on the bed; while Ott's self exists outside of a context, Sparrow's self is usually placed in a context.

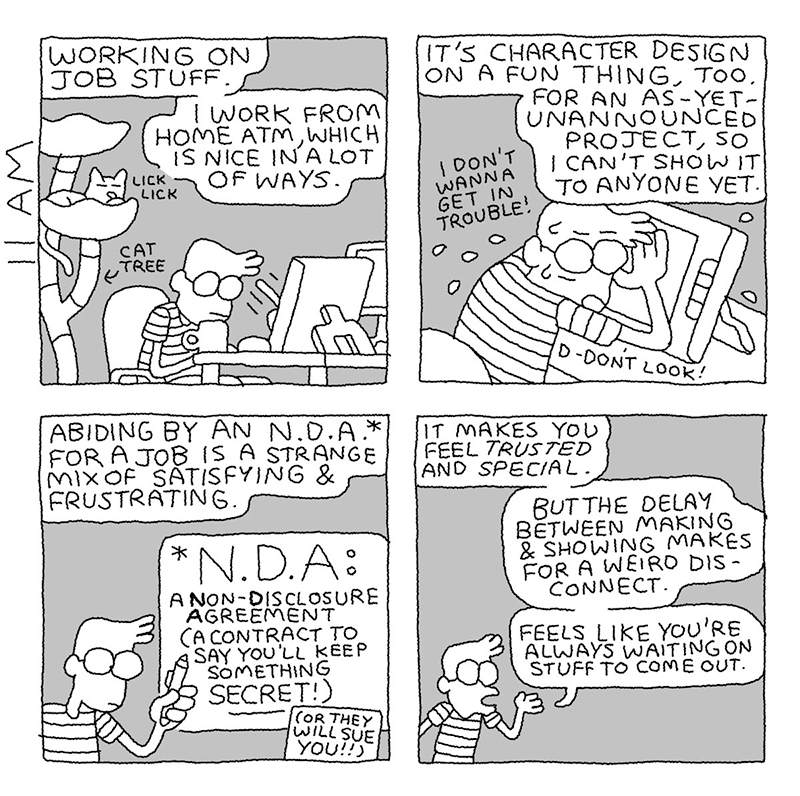

Sparrow’s work is more self-referential than Ott's; he often refers to the act of working on his hourlies and speaks directly to the reader. There is a fluidity between modes of narration, where Sparrow’s thoughts and narrative can take place in thought bubbles, speech bubbles, or separate narrative boxes. He will make use of speech bubbles to say things that he clearly did not actually say out loud, as in his 2pm strip: “I appreciate it’s a little jarring right after a strip where I joke about candy. / But it’s what I did.”.

Sparrow often elaborates on his internal monologue, justifying himself to the reader, or simply explaining something, as in his 11am strip. In this strip, Sparrow is working on work that is under a non-disclosure agreement. Even though he controls the angle from which he draws each panel, he shows himself covering his tablet screen so the reader can’t look at what he’s drawing, and then goes on to discuss what it’s like to work under NDAs. Where Ott’s hourlies are more representative of his emotional state from moment to moment, Sparrow’s read similarly to McCloud’s comic essay works, where the reader is a seemingly present audience who he speaks to in a more conversational style.

The only time Sparrow deviates from his four panel layout and consistent style is when he shows himself working between the 4pm strip to the 6pm strip. These strips are two panels each and show Sparrow at his desk, his form getting steadily more and more wobbly until he fills the lower half of the panels like static. On the first panel of the 7pm strip, he suddenly bursts out of this haze of work, remembering he had something he wanted to do. By drawing himself getting more and more lost in his work, the impact of suddenly returning to reality is more impactful for the reader and more representative of Sparrow’s experience of the event. This is something Sparrow often does in his regular work, where he tries to capture “the general overall ‘flavour’ or ‘feel’ of certain memory – trying to recreate that and communicate it to somebody” (Nobrow 2018). Sparrow was only able to achieve this effect by drawing this sequence of strips after the fact rather than throughout the day, creating more of a narrative than Ott was able to do.

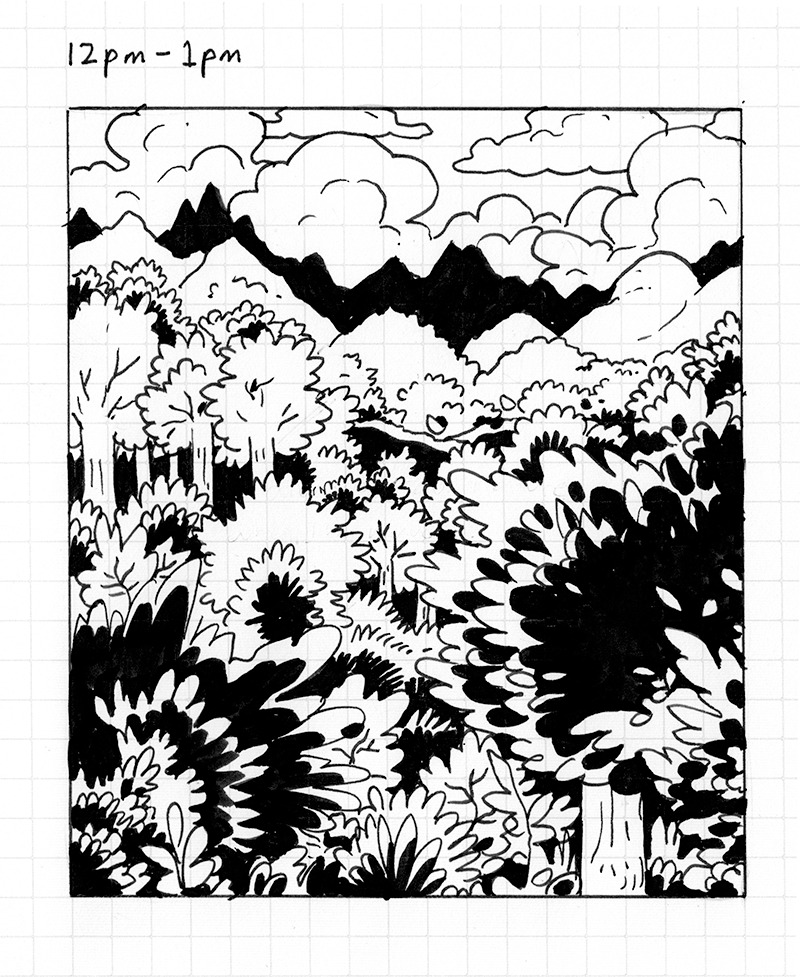

The third and final artist is Tillie Walden, a comic artist from Austin, Texas. Walden’s work has been widely congratulated on its melancholic yet ethereal tone, hugely inspired by surrealist artists like Winsor McCay (Gravett 2016). This inspiration even weaves its way into her hourlies (Walden 2018), which are full of surreal imagery and abstract shapes. They are drawn with ink on grid paper, where Ott and Sparrow’s were drawn digitally, and so they have a texture to them that reminds one of a journal. Walden has spoken about her work’s themes of being awake versus dreaming and slipping between these two states (Gravett 2016) and her hourlies reflect that; she wanders through a world where objects and moments leak into each other; her desk is surrounded by foliage, waves, and stars. For an autobiographical comic, Walden draws herself very sparsely, instead using these surreal elements to represent her thoughts; her character self is only the focus in a couple of strips. In the 11am-12pm strip, she mentions that the thought of moving house soon is overwhelming: “It’s too much. I’ll draw trees.” The following strip is a full page of trees and mountains, herself not depicted at all. Without needing further narration nor even needing to draw herself, Walden is able to give the reader a clear sense of her emotional state.

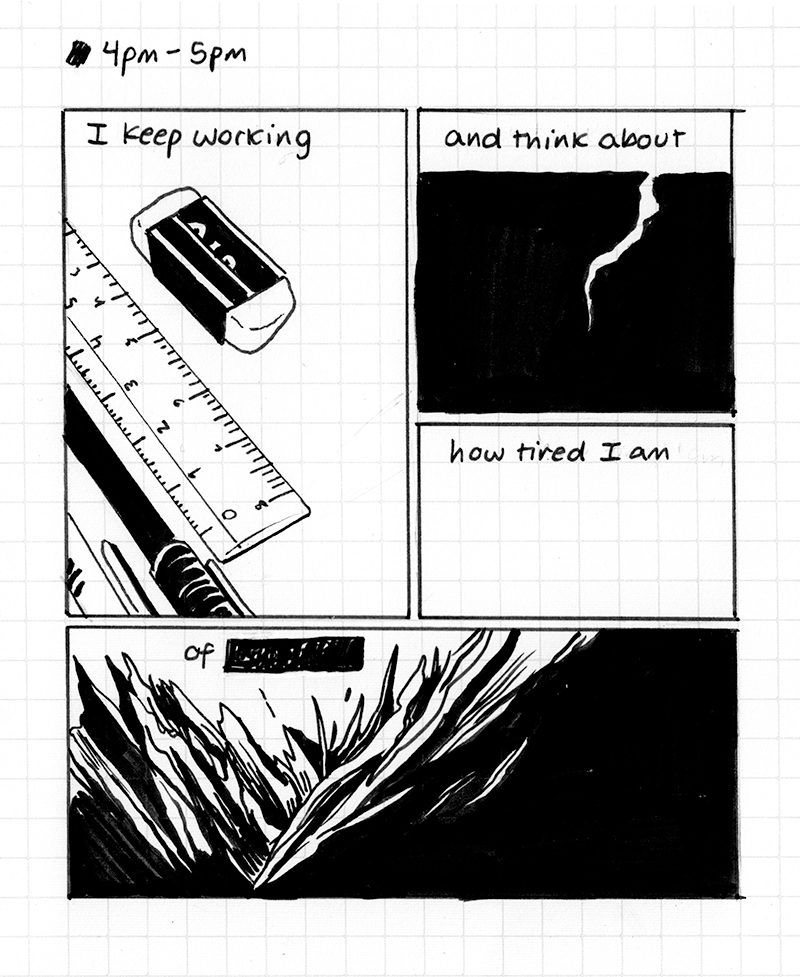

While Ott and Sparrow regularly stated what they were thinking – and, in the latter’s case, often elaborated on it – Walden keeps her private thoughts to herself, choosing instead to express them through surreal imagery. In the 4pm-5pm strip, Walden censors her own words, keeping a degree of separation between her private life and the reader while using the image to express what is clearly a negative emotion towards the subject. In this way, although the comic is not a depiction of her actual self, it is a true and accurate depiction of her inner self. This censorship and distance from the reader extends to a few other moments in the comics: the 2pm-3pm and 5pm-6pm strips are both small boxes saying “PASS” and “oh god f*** this PASS [Walden’s censoring]”, not allowing the reader to know what occurred during those hours.

That the reader is merely a visitor in Walden’s life, privy only to the details she shares with us, is recognised in her final 8pm strip: “I eat some chocolate. / and this day ends for you / but not for me.” Walden’s hourlies are less a conversation with the reader, as Sparrow’s are, and more a dreamlike window through which she allows us glimpses of her thoughts and life. Neither Ott nor Sparrow’s hourlies have an ending, they simply stop, and while Walden’s comics do not carry an overarching narrative in any traditional sense, this final sentence acts as a closing statement, firmly letting the reader know their time with Walden is over.

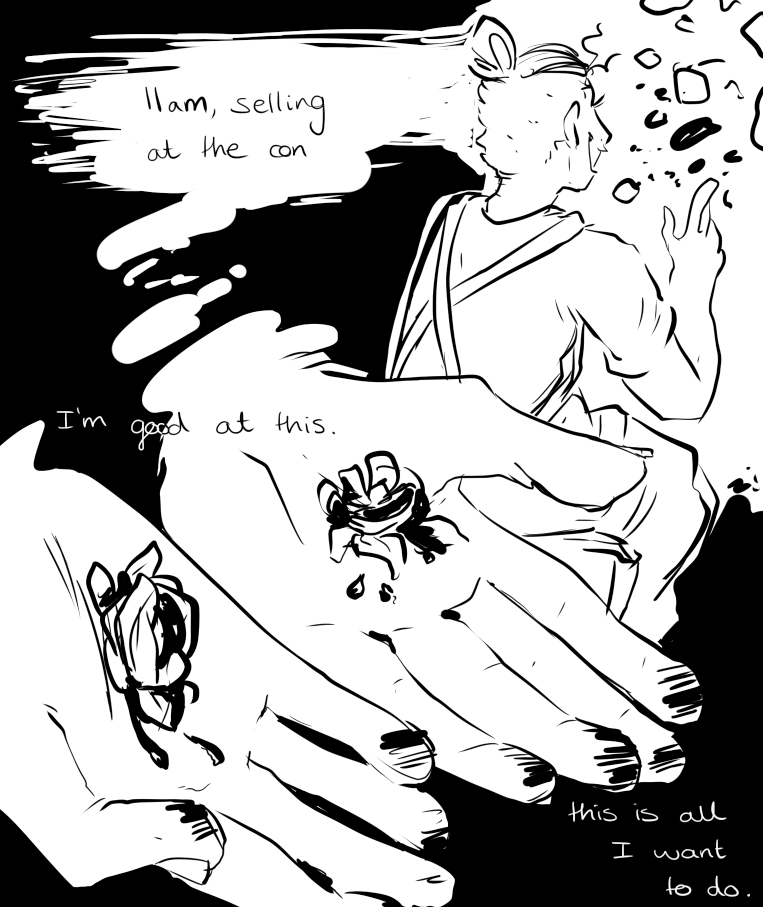

Having looked at a small sample of hourly comics, all of which depict the self in different ways and focus on different aspects of the artist’s identity, I decided to use Ott, Sparrow, and Walden’s tones and modes of self-depiction to illustrate the same moment in an autobiographical comic of my own. It was not important to mimic their artistic styles nor particular their method of drawing but the way they conveyed their selves. I also chose to limit my time to half an hour on each style and did not allow any more preplanning other than making a note of what I wanted to do for each comic. The moment I chose was tabling at a convention, an energetic and potentially overwhelming event with multiple layers of identity – salesperson, creator, student, etc. By mimicking the ways in which Ott, Sparrow, and Walden depicted themselves, I found that I was able to create a slightly different “truth” in each comic, even though all of them were true.

When mimicking Ott, I focused on using the body to represent the emotional truth of a moment. As a result, the depictions of myself hold the focus of each panel, and while the panels are very simple they each have a very clear self-perception they are conveying – the excitement and frenetic mayhem of selling and pitching, and the uncomfortable situation of forgetting someone’s name.

Mimicking Sparrow meant creating a mini narrative in four panels, as Sparrow takes a single idea or event each hour and spins it out, almost discussing it with the reader. This meant I could give the reader more insight into my thoughts at each moment rather than simply expressing how busy the con was through body language alone. Having thought bubbles, speech bubbles, and narrative boxes at my disposal meant I could layer my internal dialogue, thinking things “privately” and then turning to almost confess my poor planning to the reader. I also found myself looking for a punchline or concluding thought to finish the comic with, as Sparrow’s hourlies tend to do and perhaps encouraged by the four panel format.

Following Walden’s lead was the most difficult, as the surreal elements she makes use of in her hourlies are clearly ones she is comfortable playing with and may hold certain meaning for her. At first I tried to take direct inspiration from her use of water and plants, but it felt very forced. Constrained by time and not allowed any planning, I tried again, looser, trying to capture through imagery something close to what I felt. In Walden’s work, the focus is on the abstract self rather than an actual character self, and certain elements are left unspoken, open to the reader to interpretation, and this is what I tried to achieve here.

In conclusion, autobiographical comics rely on reinterpretation through memory to create narrative and selects which versions of the self to show to the reader in order to convey that narrative. This tradition is heightened during Hourly Comic Day, as the nature of how the comics are produced is more restricted: there is a much shorter time between event and comic; the artist is often working under a time limit; overarching narrative is often not apparent at the time and so cannot be interwoven through the strips, unless the artist is working after the events rather than an hour at a time. By looking at hourlies from three different artists, it is clear that the use of certain depictions of the self and certain narrative voices, whether conversational or distant from the reader, can affect the “truth” of an autobiographical comic, and this is further demonstrated when the three methods of self-depiction are used to depict the same event. The number of artists who take part in Hourly Comic Day grows every year, and with so many working under the same conditions this essay barely scratches the surface of how one may choose to convey one’s identity through autobiographical work.

References

- Bechdel, Alison, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (2006 Houghton Miffin).

- Chute, Hillary L., “Scratching the Surface: “Ugly” Excess in Aline Kominsky-Crumb” in Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics (2010 Columbia University Press) (web, available here in April 2018).

- Jacobs, Dale, Multimodal Constructions of Self: Autobiographical Comics and the Case of Joe Matt’s Peepshow (2008: University of Windsor) (web, available here in April 2018).

- El Refaie, Elisabeth, “Of men, mice, and monsters: body images in David Small’s Stitches: A Memoir”, in Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 3:1 (2012 Routledge) (pp. 55-67).

- Gravett, Paul, “Tillie Walden: That In-Between State”, on Paul Gravett (2016) (web, available here in April 2018).

- Kominsky-Crumb, Aline, “Up in the Air” in Love That Bunch (2000 Fantagraphics Books).

- McCloud, Scott, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (1994 Kitchen Sink Press).

- Millan, Roberto, Illustrating Autobiography: Rearticulating representations of self in Bitterkomix and the visual journal (2012 Stellenbosch University) (web, available here in April 2018).

- Nobrow, “Joe Sparrow” (2018) (web, available here in April 2018).

- Ott, Cole, Hourly Comics 2018 (2018) (web, available here in April 2018).

- Small, David, Stitches: A Graphic Memoir (2009 WW Norton & Company).

- Sparrow, Joe, Hourly Comics 2018 (2018) (web, available here in April 2018).

- Walden, Tillie, Hourly Comics 2018 (2018) (web, available here in April 2018 (no archived page available)).

- Weiss, Gail, Body Images: Embodiment as Intercorporeality (1999 Routledge).