Another write-up I wanted to archive. This was an essay I wrote for my Comics & Graphic Novels MDes degree in 2018. I have linked to a PDF of this in the past but wanted to archive it as an article/blogpost as well. Any references made were accurate at the time of writing - sadly a few of these comics have either been cancelled or lost. Enjoy!

The evolution of comics as an art form is clearly trackable throughout history. From the arguable father of the modern comic, Rodolphe Töpffer, to the newspaper funnies, to the superheroes and graphic novels of the late 20th century, comics have rapidly changed and adapted thanks to the opportunities provided by new printing technologies. Now, with the advancement of the digital age, comics are being brought into a digital medium and are being explored and expanded upon in ways that have been thus far impossible. Although they do share elements with traditionally printed comics, digital comics – particularly webcomics – make use of non-traditional format and extra-narrative elements in order to heighten the comic-reading experience. These extra- narrative elements include controlling the pacing of reading, retcons, site layouts, and animation.

First, however, it is important to define what is meant by the term “webcomic”. In this essay, “webcomic” will be used to denote a comic that was made to be read digitally[1] – it is often the case that webcomics are published online with the ultimate intent of being printed traditionally, but they are first seen on the screen and print versions may be altered to fit the print format and may therefore forgo certain elements of the original comic. It is, however, far easier to narrow down what constitutes a webcomic by explaining what it is not. A webcomic is not necessarily drawn digitally; comics such as Prague Race[2] by Finnish creator Petra Nordlund are drawn traditionally with ink and scanned in. A webcomic is not necessarily a gag-a-day strip; many webcomics are longform narratives, although there is also a proliferation of gag-a-day comics that carry on the tradition of newspaper funnies, such as Our Super Adventure[3] by English creator Sarah Graley. It is common for a webcomic to be released slowly over a long period of time, most typically at a page a week or perhaps several pages every few weeks, rather than the entire comic being available to read in one go. A webcomic is also not a genre, but a medium; it is impossible to say one does not enjoy webcomics, as the term encompasses comics of all genres. It is important to remember that just as the traditional printing method has its own advantages and disadvantages, the same can be said for webcomics. The comparison of print and digital is the same as the comparison between an oil painting and a watercolour painting; one is not inherently lesser because of the material that is used to create it. Digital comics are often seen as illegitimate comics, seen as trying to simply copy traditional comics, when they in fact have their own style and format conventions, reader xpectations, and possibilities as a medium. Companies such as Marvel and Comixology are trying to jump on the digital comics train by introducing PDF versions of print comics, but these are simply traditional comics readapted for the screen and are not true webcomics as will be discussed here. The webcomic industry is larger and more vibrant than it has ever been, and comic readers do it a disservice to simply dismiss webcomics as substandard to “real” comics.

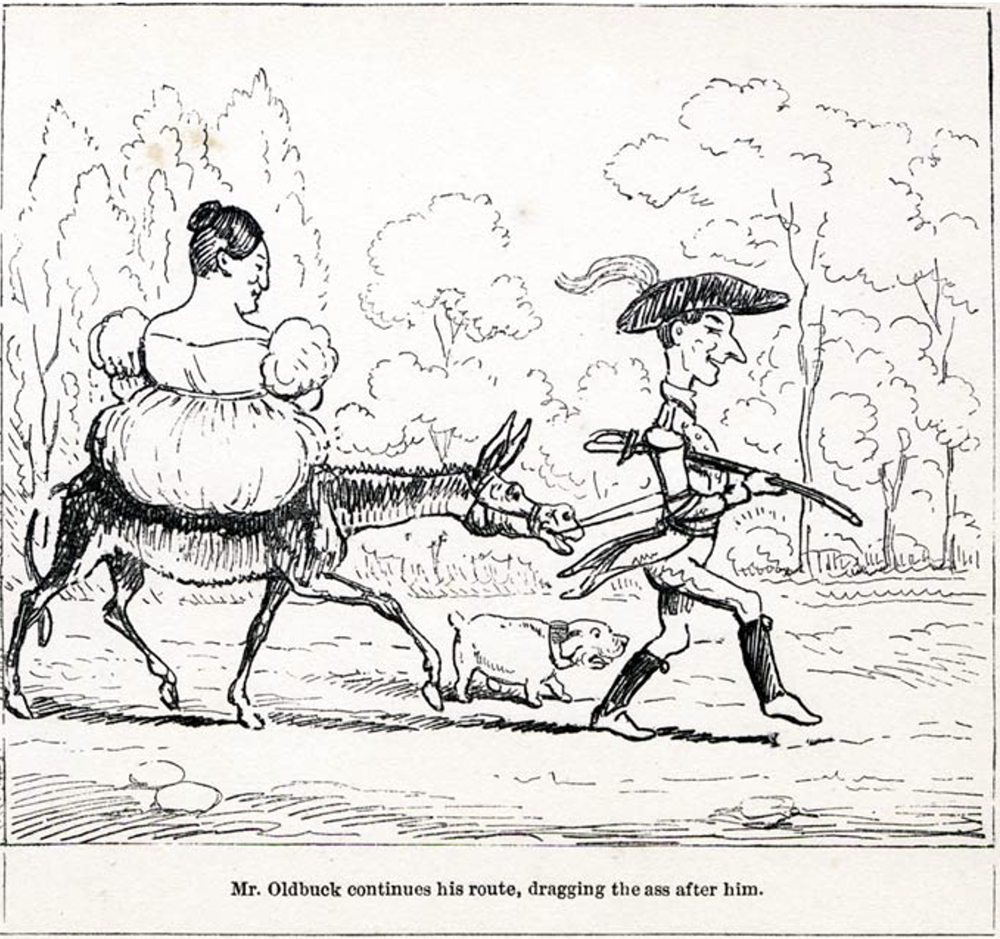

When discussing webcomics and their breaking of traditional comics format, it is near impossible to go without mentioning Homestuck[4], a sprawling behemoth of a story created by Andrew Hussie. Homestuck spans 8126 pages, featuring 14,915 panels and 817,925 words[5], and ran from 2009 to 2016. The standard layout for a page was a single textless panel of consistent size with an accompanying caption, either written as narration in the second person or with character dialogue, written as a chatlog. These pages are reminiscent of early comics featuring a single image and a related caption underneath – Töpffer’s 1842 comic M. Vieuxbois, for example.

M. Vieuxbois |

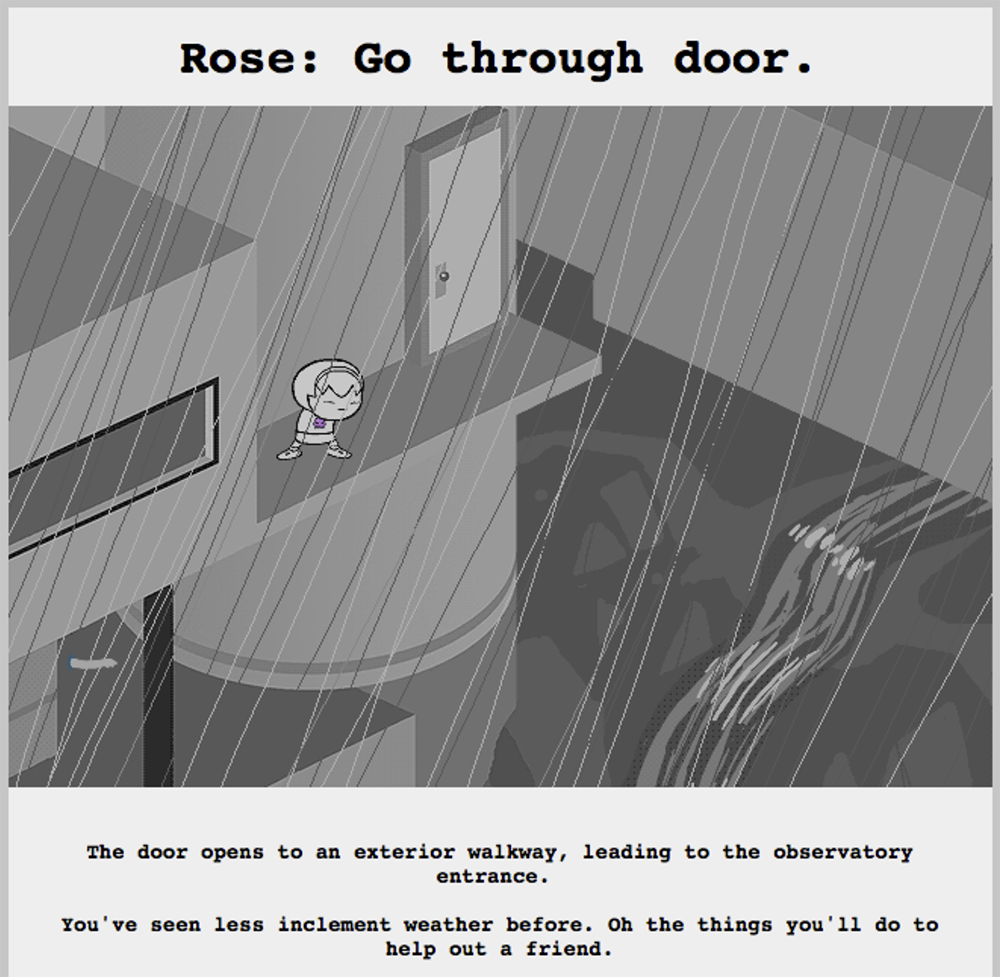

Homestuck, p. 2133 |

As the comic progressed, Hussie began to include the occasional lengthier animation, some of which lasted several minutes and included custom music. A number of narrative flash games were also created to take the place of certain pages. Naturally, animation and games transcend the comics format, but Homestuck cannot go unmentioned, having inspired a new generation of webcomics that eschewed traditional modern page layouts, such as Danny and Shelby Cragg's Neo-Kosmos[6] or Michelle Czajkowski's Ava's Demon[7].

Neo-Kosmos

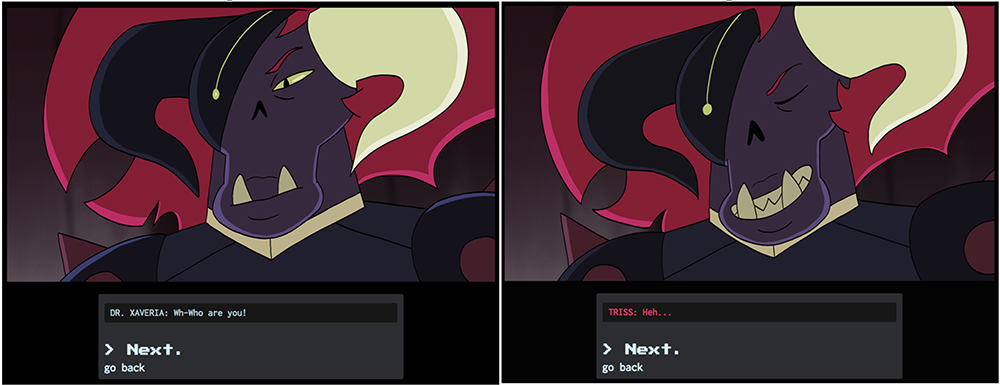

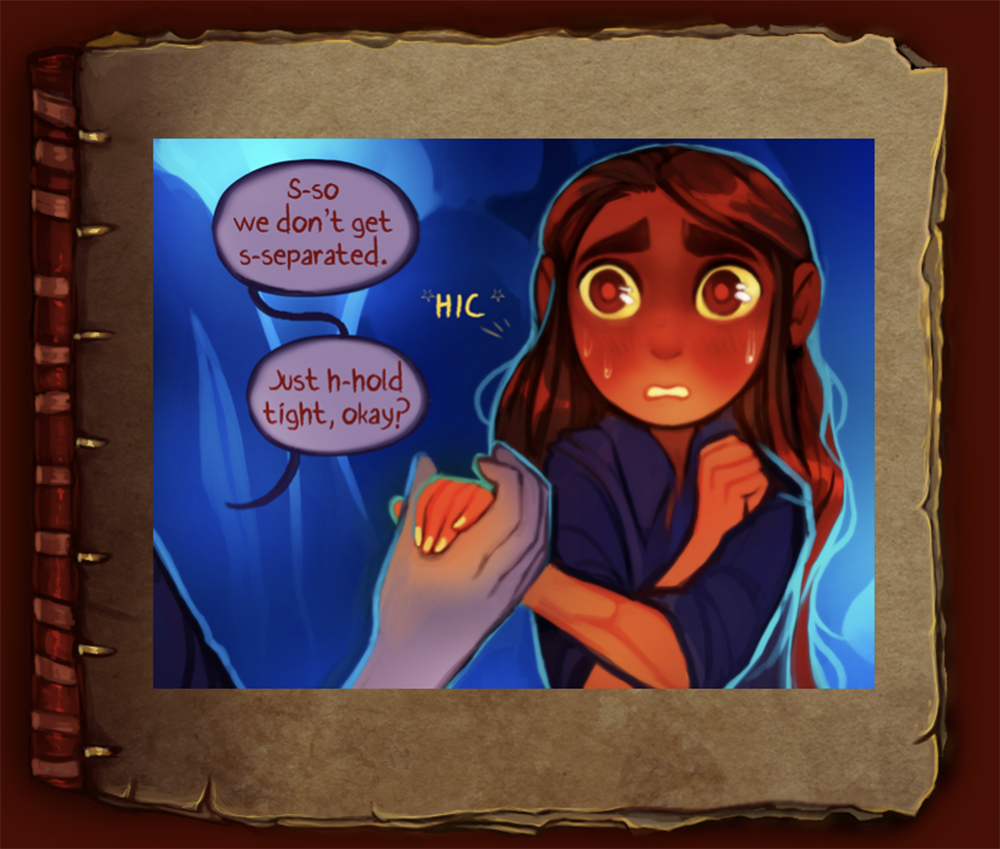

The consistent panel size of this style of comic seems to act almost as storyboards, acting out moments beat for beat and perhaps therefore losing out on the effect of the gutter and panel size to convey time and importance of moments. Ava’s Demon is able to avoid layout stagnation by altering the panel shape and orientation to indicate mood shifts. The standard page is a panel displayed within a book, as shown on page 1129.

Ava's Demon, p. 1129 |

Ava's Demon, p. 1130 |

Ava's Demon, p. 1132 |

Ava's Demon, p. 1134 |

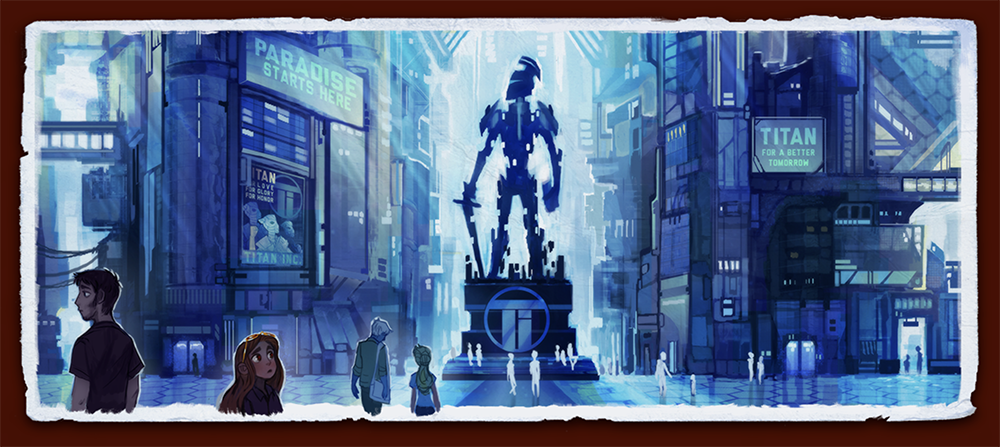

In order to convey the mental turmoil of Ava, the main character, Czajkowski adds a collage-like element to the scene that becomes more and more intrusive, ultimately taking over from the book entirely. This scene is made all the more effective by the fact that Czajkowski only deviates from the standard panel size for very specific moments, such as Ava’s arrival at TITAN’s imposing headquarters (page 1035). In this way, Czajkowski is able to use the single panel format but retain the same effect as interesting panel compositions in comics with a more traditional page layout.

Ava's Demon, p. 1035

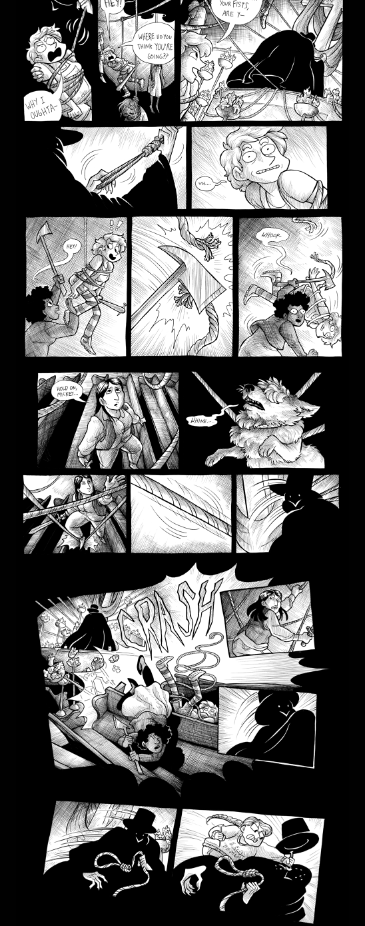

On the opposite end of the spectrum, some webcomics make use of the endless space available to them on a screen. Your Worst Nightmare[8] by German creator San and The Last Halloween[9] by American creator Abby Howard both feature long vertical strips which make up a single “page” (The Last Halloween was created with a print book in mind, however, and so panels are still arranged in such a way that they could easily be split into standard pages). It is interesting to note that Western webcomics in a vertical format often retain the panel layout of a traditional comic page, where a single row can contain multiple panels, resulting in the eye navigating the page in a Z-shaped pattern. Vertical webcomics posted on Korean hubs, however, tend to adhere to the Korean webcomic single-panel layout, such as in Finnish creator Susanna Nousiainen’s Shootaround[10], published by LINE Webtoon.

The Last Halloween, section of p. 132 |

Shootaround, section of p. 135 |

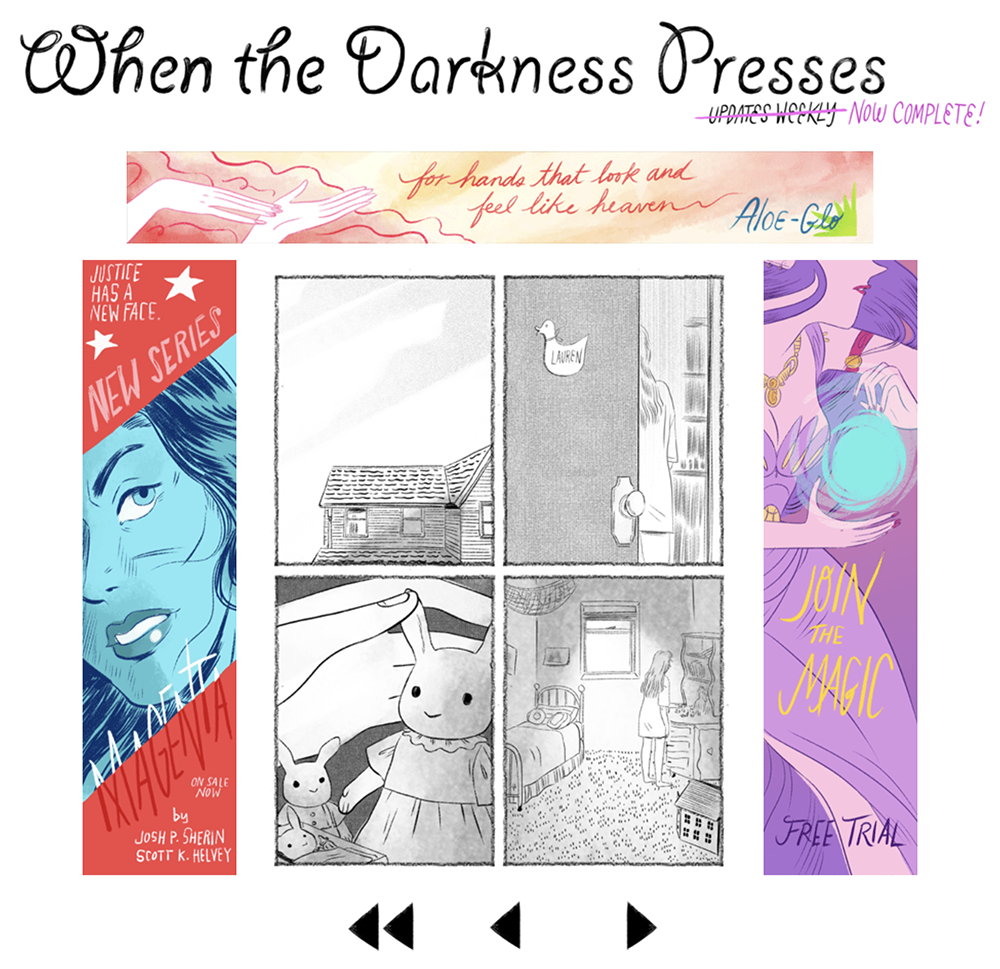

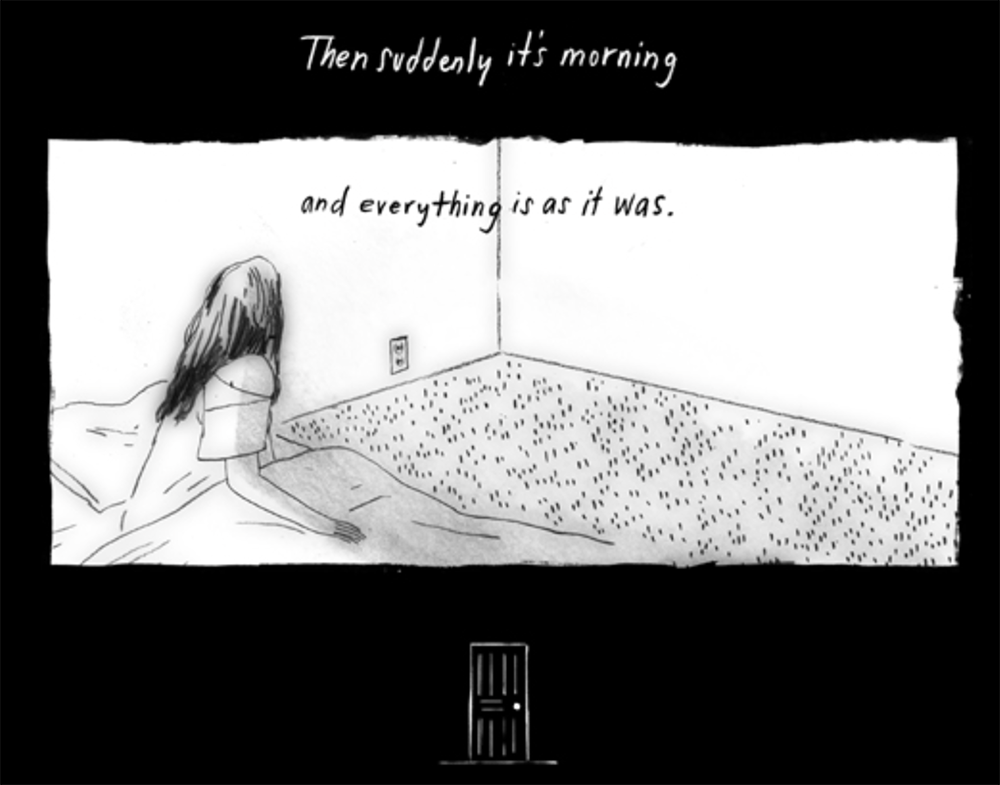

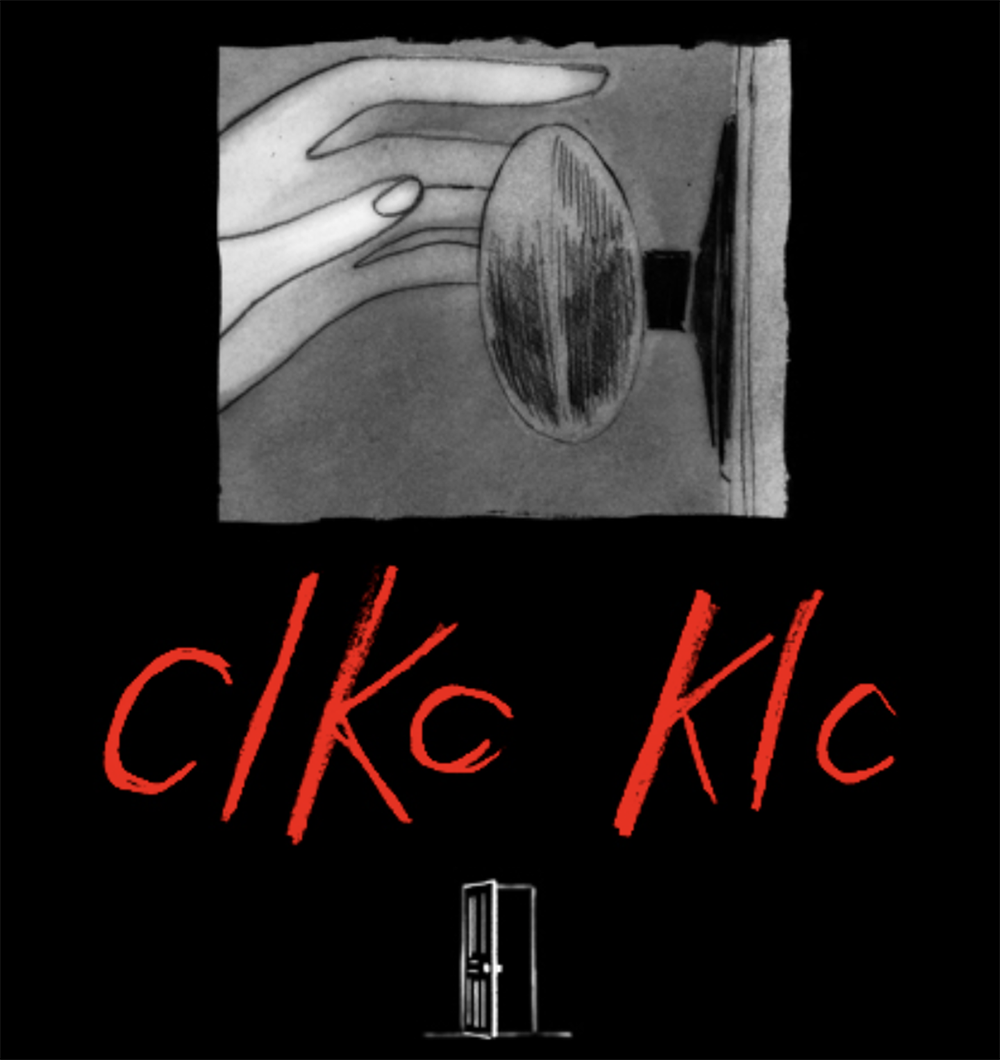

One of the masters of the free-space webcomic format is Canadian horror writer Emily Carroll, whose deeply unsettling work takes advtange of the digital medium in very subtle ways. Her short 2014 comic When the Darkness Presses[11], in which the main character is plagued by nighttime terrors and dreams of a closed door, features traditional single-panel layouts as well as both verticl and horizontal scrolling; when the main character finally opens the door, the orientation switches to a horizontal format and forces the reader to scroll left to right, disorienting them and adding to the unusual dreamlike quality of the sequence.

When the Darkness Presses

As well as playing with both traditional and non-traditional comic formats, webcomics can make use of a number of extra-narrative elements that enhance the reading experience. The first of these, and perhaps the most obvious, is the site layout and its related features, such as the site URL and navigation buttons. While the site can act as a hub for the comic and is therefore often designed to match the theme of the comic, the layout can also be inextricably interwoven with the narrative, as with When the Darkness Presses. The daytime scenes mimic a traditional webcomic site layout, with the title and update schedule at the top and fake advert banners surrounding the page itself. The nighttime scenes, however, revert to Carroll's eerie vertical scrolling pages with stark black backgrounds.

When the Darkness Presses |

When the Darkness Presses |

One of the most subtle ways in which Carroll uses the layout to enhance the narrative is through the navigation buttons. On the "regular" site, the navigation buttons are arrows, with options to go back and to start again. At night, however, the forward arrow is replaced by the door that the main character is dreaming about, and the option to go backwards is removed. In a later sequence, when she goes to open the door, the next page button is replaced by an open door that the reader must click to progress the story and the layout begins to distort, the adverts from earlier pages being brought in but altered to look bloody and violent. These creative methods of unsettling the reader go beyond the content of the comic alone.

When the Darkness Presses |

When the Darkness Presses |

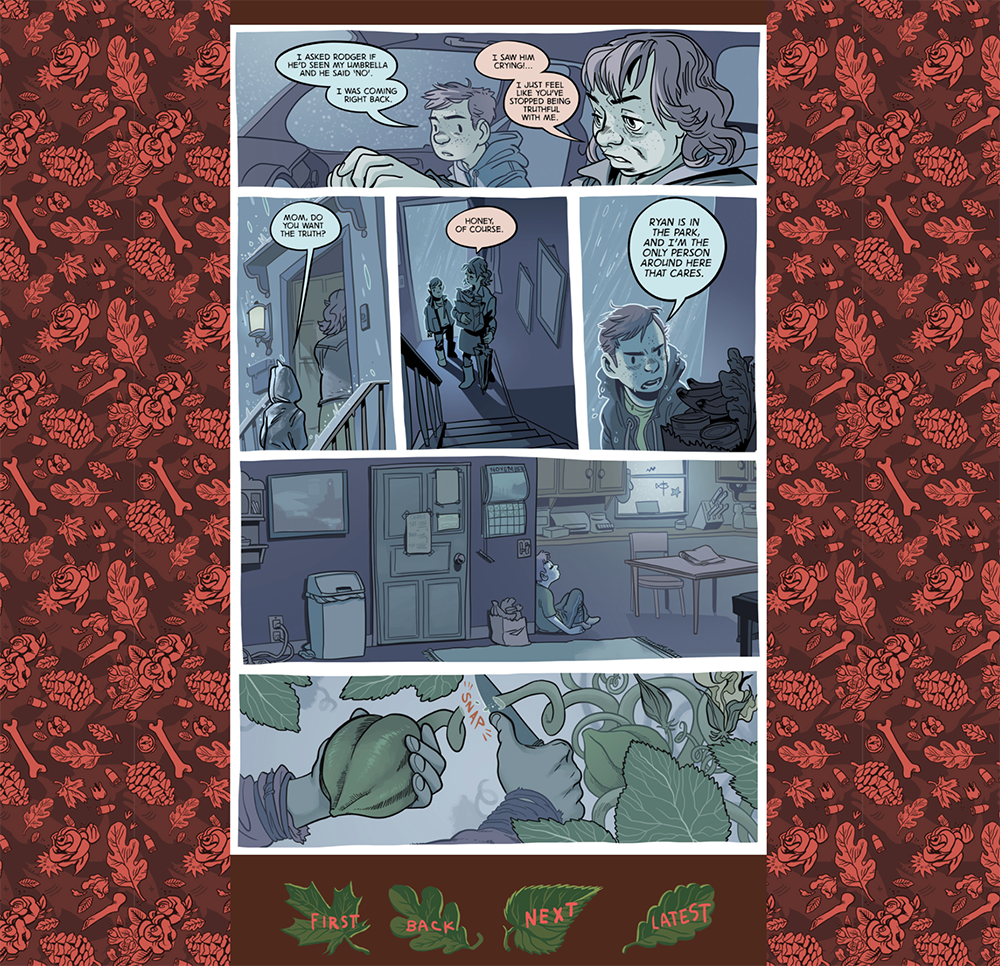

Another example of the successful manipulation of site layout can be seen in American creator Jonas Goonface's Follow the Leader[12]. This webcomic is formatted in a more traditional page style and tells the story of a town haunted by the child cannibals that live in the adjacent forest. The forest is a constant presence in the back of the townsfolk's minds, and it becomes present in the reader's mind too; the looming threat of the surrounding forest is reflected in Goonface's stark choice of site layout, endlessly reminding readers by the intense layout that frames each page and navigation buttons, which are shaped like leaves rather than directional arrows. As a result, the town of the comic is one of constant unease, even when the scene is not taking place in the forest itself or no violence is being depicted on the page. Print copies of Follow the Leader are available and of course these lack the background found on the site, resulting in a different and potentially less involved reading experience. It is clear, however, that Goonface makes use of the layout to convey the theme and tone of the comic and thereby add a layer to the reader's understanding of the story.

Follow the Leader

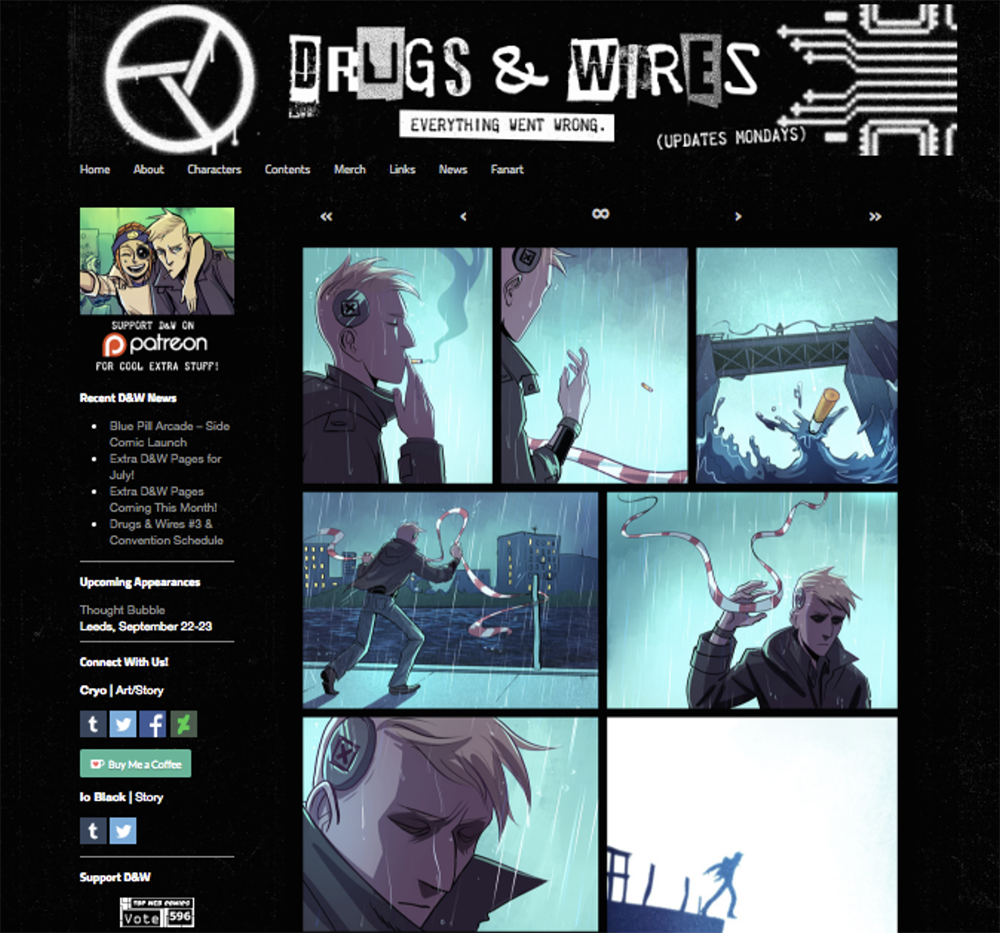

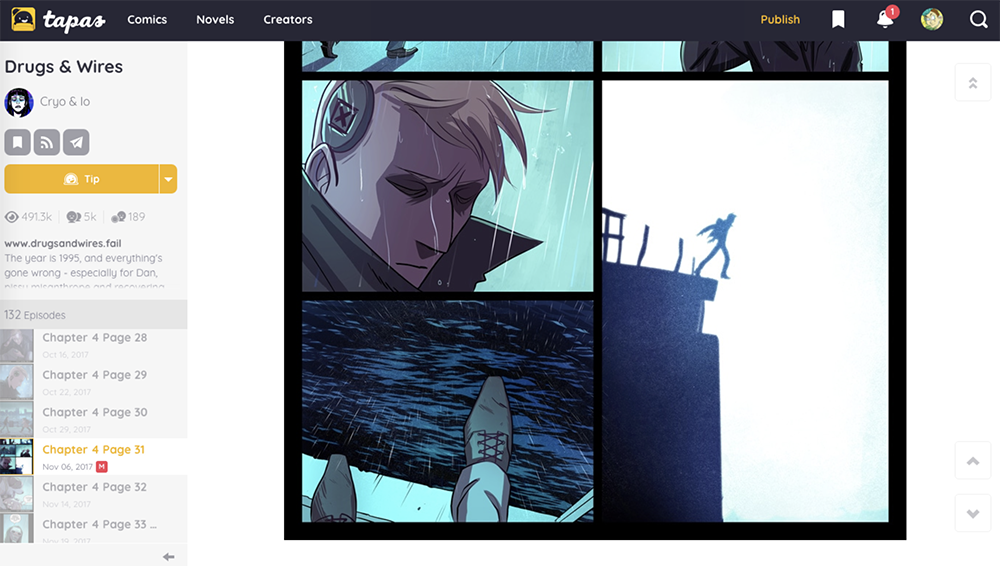

Considering that a site layout can certainly work with a comic's tone or act as part of the narrative itself, it is then interesting to discuss whether or not a layout can detract from the reading experience. A print comic can exist as a separate physical object, but a webcomic is tied to its layout. Although some webcomics are housed on their own sites, as seen previously, other creators may choose to upload or mirror their comics on subscription sites with a pre-existing reader base. These sites often do not allow custom layouts, however, and pages may lose their impact as a result. Compare, for example, the following pages from Drugs & Wires[13], by Latvian artist Mary Safro and German writer Io Black, the first of which is posted on the main website and the second on Tapas, which they are using as a mirror site. In this page, the main character, Dan, is attempting to commit suicide.

Drugs & Wires, ch. 4 pg. 31

Drugs & Wires, ch. 4 pg. 31

Where the creators are able to set a tone for the comic on their own website, with the title banner and stark black background, the clashing UI and white background of the Tapas mirror detracts from the seriousness of this scene. As readers can subscribe to comics on Tapas to be notified when they update, there is also a notification bar at the top of the page, which may distract readers’ attention. Of course, the difference between layouts is minimal, considering that both have a sidebar with links, but the extent to which a surrounding layout can draw a reader into the story or serve to lessen a story’s impact is something that cannot be analysed in traditional print comics and is therefore interesting to look at.

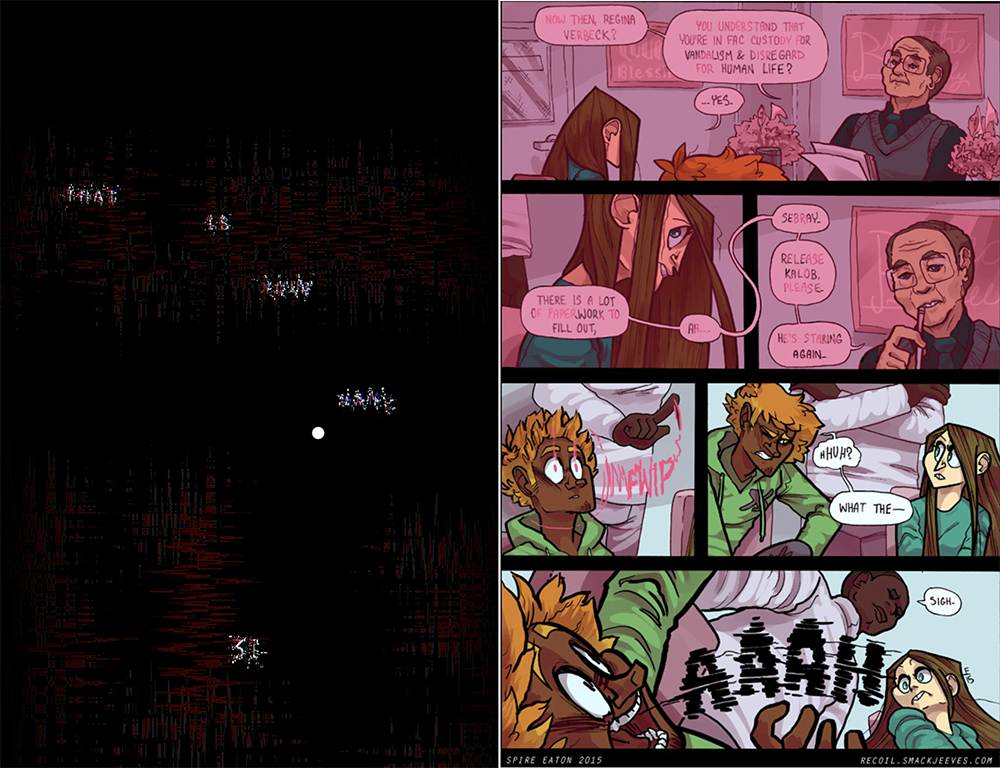

Another feature of webcomics that cannot be translated into in print comics is retconning pages - that is, playing with retroactive continuity. This can be done with narrative, of course, but not with the actual physical comic itself. One of the most interesting examples of this is in Recoil[14] by American creator Spire Eaton. Recoil follows a boy called Kalo who discovers he has superpowers and is taken to a medical facility. Over the course of the comic, we discover that, unbeknownst to him, he is being hypnotised by the head of the facility, resulting in disorientation and loss of memory. Eaton extends this disorientation to the reader by retroactively adding pages that indicate Kalo is undergoing hypnosis between scenes that, when the pages were originally sted, the reader was not aware of. The page on the right shown here was originally the first page of the third chapter, where Kalo first arrives at the facility. The reader was aware that he was being controlled like a puppet in order to be brought there, but did not yet know that he had also at this point undergone hypnosis. When it was revealed two and a half years later that he was being hypnotised, Eaton added the page on the left just before page 1, titled “page 0131”, Kalo’s number in the facility. Such additions were not pointed out and work to disorient those who have been following the comic and choose to reread, making them wonder if their memory is as faulty as Kalo’s. Other changes included making letters in the site banner occasionally flicker and change into the number 31. These extra-narrative details heighten the reading experience, particularly for regular readers rather than those who read the comic all in one go.

Recoil, ch. 3 p. 0131 and ch. 3 p. 1

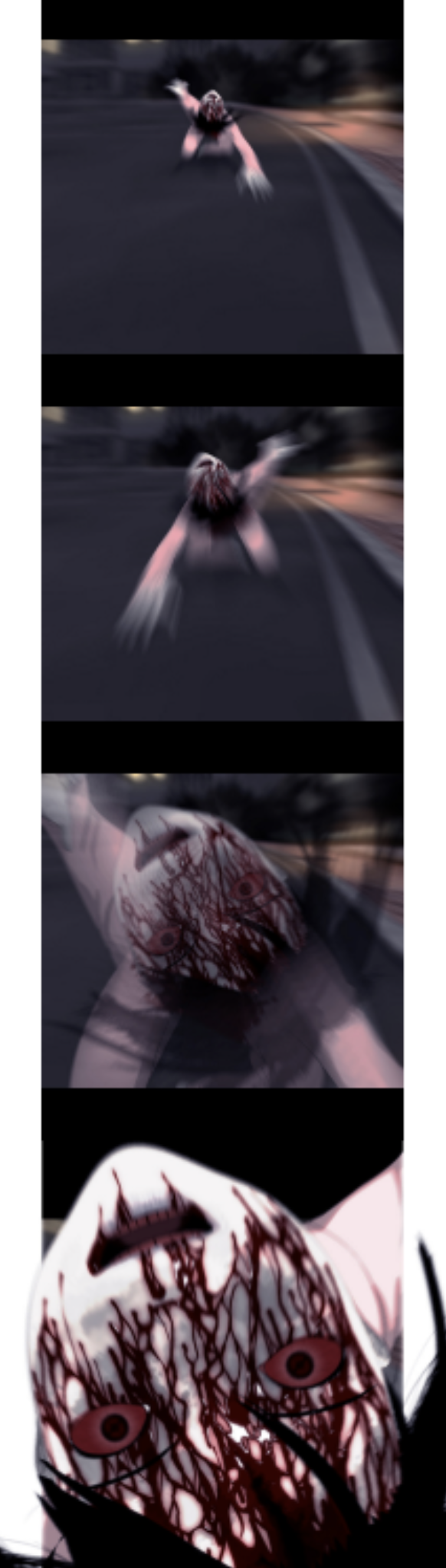

A feature unique to comics, one that most readers take for granted, is the controlled pace of reading. Unlike moving image or traditional literature, a comic reader can control the pace at which events unfold by lingering or skimming over panels as they desire. Where an artist can stretch or squash time by increasing the number of panels a moment takes up or diminishing it to a single panel, it is ultimately up to the reader how fast time actually passes, including when to turn the page. Japanese horror artist Junji Ito makes use of the reader’s control over the narrative to his advantage in many of his stories, as video essayist John Walsh explains: “Right when something bad is about to happen, [Ito] always gives us this little panel right at the bottom of the page of our character reaction to something unseen. And then it’s up to us to turn the page[15].” By handing the reins directly to the reader, Ito is using the traditional comics medium to create more fear, or a different kind of fear, than possible in mediums such as film where the viewer is not at all in control. Webcomics can create a similar effect by forcing a reader to choose when to click to the next page, such as in Carroll’s work, but it is also possible for them to wrest control entirely out of the readers’ hands. This is especially effective in the 2011 horror comic Bongcheon-Dong Ghost[16] (right), created for Korean webcomic publisher Naver Webtoon. As is standard for Korean webcomics, the comic is comprised of single panels arranged vertically and the reader must scroll down to read, but at certain moments the site takes over and suddenly speeds up the scrolling to zip past several panels, creating the effect of the ghost turning around or rushing at the reader. This sudden movement, paired with the sound of the ghost and the fact that the final panel of the second jumpscare has the ghost moving past the boundaries of the panel border that the rest of the comic stays behind, is frightening because it is unexpected not only because it surprises the reader but also because it creates a sense of helplessness in a medium where the reader is usually entirely in control.

A feature unique to comics, one that most readers take for granted, is the controlled pace of reading. Unlike moving image or traditional literature, a comic reader can control the pace at which events unfold by lingering or skimming over panels as they desire. Where an artist can stretch or squash time by increasing the number of panels a moment takes up or diminishing it to a single panel, it is ultimately up to the reader how fast time actually passes, including when to turn the page. Japanese horror artist Junji Ito makes use of the reader’s control over the narrative to his advantage in many of his stories, as video essayist John Walsh explains: “Right when something bad is about to happen, [Ito] always gives us this little panel right at the bottom of the page of our character reaction to something unseen. And then it’s up to us to turn the page[15].” By handing the reins directly to the reader, Ito is using the traditional comics medium to create more fear, or a different kind of fear, than possible in mediums such as film where the viewer is not at all in control. Webcomics can create a similar effect by forcing a reader to choose when to click to the next page, such as in Carroll’s work, but it is also possible for them to wrest control entirely out of the readers’ hands. This is especially effective in the 2011 horror comic Bongcheon-Dong Ghost[16] (right), created for Korean webcomic publisher Naver Webtoon. As is standard for Korean webcomics, the comic is comprised of single panels arranged vertically and the reader must scroll down to read, but at certain moments the site takes over and suddenly speeds up the scrolling to zip past several panels, creating the effect of the ghost turning around or rushing at the reader. This sudden movement, paired with the sound of the ghost and the fact that the final panel of the second jumpscare has the ghost moving past the boundaries of the panel border that the rest of the comic stays behind, is frightening because it is unexpected not only because it surprises the reader but also because it creates a sense of helplessness in a medium where the reader is usually entirely in control.

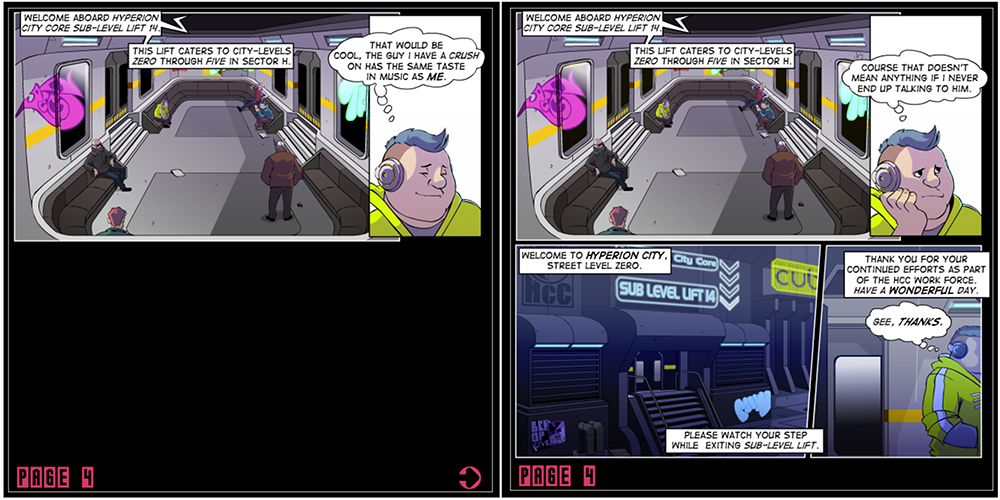

Controlling the reading pace does not have to be a negative thing, however. Casey J.’s webcomic Buying Time[17] acts as part animation, part comic, with one panel or speech bubble appearing at a time and the reader having to click to make the next panel appear. While at first glance one would imagine that the comic could be fully replicated in print form, it is not so simple; some panels include small animations, such as an elevator arriving, or a single panel will cycle through a couple of different speech bubbles as the dialogue goes on, as seen below, meaning that one cannot read a “finished” page and get the whole story. Not only is this a creative way to manipulate the time a reader must spend on a single panel or moment, but it further demonstrates the ways digital comics can play with elements that are predetermined in traditional comics.

Buying Time, p. 4

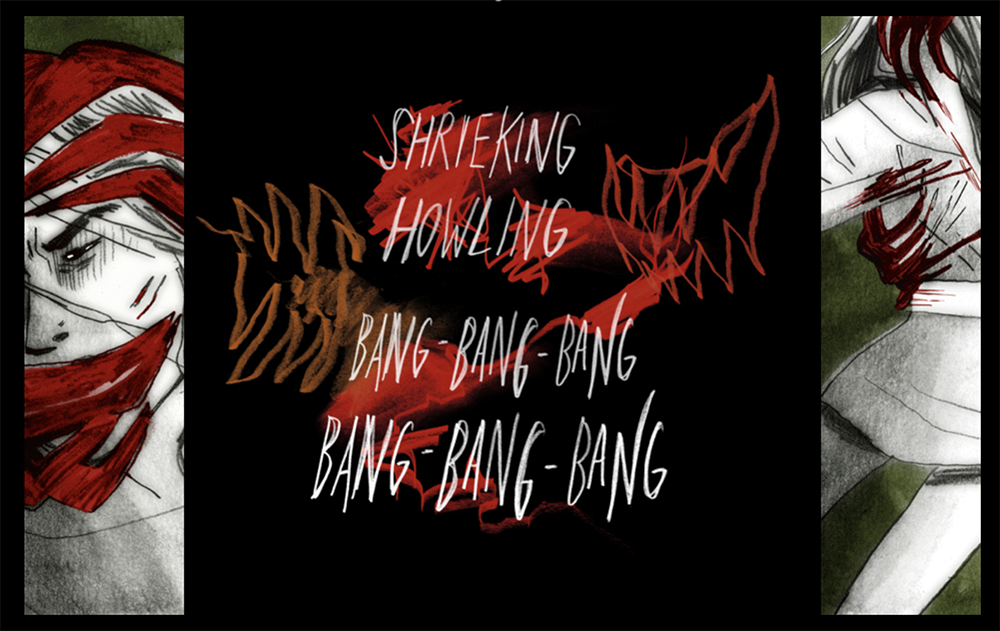

When people think of webcomics and what they can do that one cannot do with print, the first thing that comes to mind is probably sound and animation, and for that reason it has been left to last in this discussion. Comics such as Homestuck employ sound and animation to such a great degree that they become true transmedia narratives, blurring the boundaries between art forms. When used sparingly, however, animation can enhance the comic-reading experience in meaningful ways. As an example, let us take another look at Safro and Black's Drugs & Wires. Dan is a VR addict whose brain implant that allows him to access virtual reality is glitchy, giving him hallucinations. The comic makes use of many 90s-style 3D models and computer elements, but the only time we see actual animation is when Dan's implant glitches. Naturally, it is impossible to reproduce the effect in this essay, but the below scene makes use of a flashing glitch effect in the bottom left panel and the right panel judders violently. Rather than being distracting, these elements allow the reader to experience what Dan is seeing and heighten the tension of the moment. Print copies of this scene, again, cannot include the animation and this does not detract from the story, but the effect of experiencing Dan's glitch for themselves brings the event to life in a way that seeing a still image cannot replicate.

Drugs & Wires, ch. 4 pg. 5

In conclusion, webcomics are able to make use of extra-narrative elements that are not present in traditional print comics. These elements include varied page size and orientation, site layout, retcons, controlled pace of reading, and animation. These elements may not be necessary to the story but serve to more deeply immerse the reader, such as in Follow the Leader , or may act narrative devices intrinsic to the story, such as in When the Darkness Presses. For these reasons, it is laughable to say that by simply reading a comic on a screen one is engaging in an inherently lesser form of comics. The extent to which webcomic creators have explored the possibilities of the screen is fascinating, and yet there are are always new and exciting ways to make use of the digital medium. Comics and zines have already found popularity among marginalised creators due to their accessible nature but webcomics, most of which are free to read online, are even more accessible to both readers and creators alike. A large number of webcomic creators are queer and/or creators of colour, and are therefore able to share their experience and stories without having to worry about editors or finding a publisher willing to take on the material. These stories are finding an enthusiastic audience with readers who have thus far been let down by mainstream or traditional comics. With the endless potential of technology and hundreds if not thousands of webcomics still to be created and artists and writers whose stories are yet to be told, it will be a delight to see how webcomics continue to break free of the constraints of traditional comics.

Footnotes

[1] Please also note that due to the nature of webcomics, it is not always possible to be consistent when referring to specific pages. As such, this essay will refer to page number or the date a page was posted as much as possible, but if there is no page or date then this information is not available.

[2] Nordlund, Petra, Prague Race (ongoing, 2009-2018: Hiveworks) (web, available at http://praguerace.com).

[3] Graley, Sarah, Our Super Adventure (ongoing, 2013-2018) (web, available at http://oursuperadventure.com).

[4] Hussie, Andrew, Homestuck (ongoing, 2009-2016) (web, available at http://www.mspaintadventures.com).

[5] Bailey, Anthony, "MS Paint Adventuers: Statistics" on Read MS Paint Adventures (2018) (web, available at http://readmspa.org/stats).

[6] Cragg, Danny, and Cragg, Shelby, Neo-Kosmos (2015-2018) (web, available at http://www.neo-kosmos.com).

[7] Czajkowski, Michelle, Ava's Demon (ongoing, 2012-2018) (web, available at http://www.avasdemon.com).

[8] San, Your Worst Nightmare (ongoing, 2015-2018) (web, available at https://www.webtoons.com/en/challenge/your-worst-nightmare/list?title_no=33483).

[9] Howard, Abby, The Last Halloween (ongoing, 2013-2018) (web, available at https://www.last-halloween.com).

[10] Nousiainen, Susanna, Shootaround (2015-2017: LINE Webtoon) (web, available at https://www.webtoons.com/en/drama/shoot-around/list?title_no=399).

[11] Carroll, Emily, When the Darkness Presses (2014) (web, available at http://emcarroll.com/comics/darkness).

[12] Goonface, Jonas, Follow the Leader (ongoing, 2014-2018) (web, available at http://followtheleaderwebcomic.tumblr.com).

[13] Safro, Mary, and Black, Io, Drugs & Wires (ongoing, 2015-2018) (web, available at http://drugsandwires.fail).

[14] Eaton, Spire, Recoil (ongoing, 2014-2018) (web, available at https://recoil.one).

[15] Walsh, John, "How Media Scares Us: The Work of Junji Ito" on Super Eyepatch Wolf (2016) (video, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lIIA6QDgl2M).

[16] HORANG, Bongcheon-Dong Ghost (2011: Naver Webtoon) (web, available at http://comic.naver.com/webtoon/detail.nhn?titleId=350217).

[17] J., Casey, Buying Time (ongoing, 2013-2018) (web, available at http://buyingtime.the-comic.org).